Washington

Reconstruction Vignette

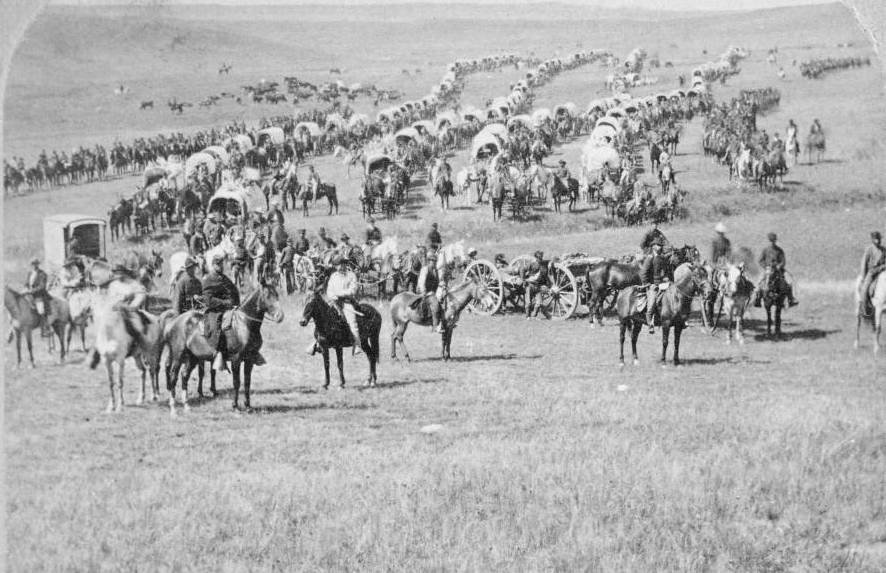

| As postwar Washington set out to consolidate the nation into a tighter, truer union, its efforts out West simply had no developed option that would leave room for people like the Nez Perces — historically friendly and utterly unthreatening but living by ways well outside the national mainstream — to live as they wanted while still being part of that new union. Some official like Howard might begin by saying some peaceable people should be left alone in some “poor valley,” but then came pressure to open that valley up, and then some nasty business like the killing of Wilhautyah to force a decision. At that point, authorities had no structure of ideas to accommodate anything but pulling Indians onto some reservation. Language changed. “Sympathy” and “fairness” took on new meanings. Honest men and women, sympathizers with the deplorable things happening to Indians, insisted that they be fairly paid for their land and fairly supported as they built new lives. But whether Indians would surrender their land and change their lives — that was not in the discussion. When people like the Nez Perce resisters stuck to their claims, the reaction of authorities like Howard was to feel dismayed, frustrated, and, in a deeply strange inversion, betrayed. |

When Congress terminated the Freedmen’s Bureau in the early 1870s, the federal government increasingly directed its attention and resources to settler colonial expansion and “civilization” in the West. General Oliver O. Howard, a former commander in the Union Army and head of the Bureau, rejoined the military to direct the removal of Native people to reservations in the Pacific Northwest. The Nez Perce, whose homeland included part of present-day Washington, refused to give up their sovereignty. Under Howard’s order, communications devolved into violence and Native removal in 1877. Howard and other Republican leaders had twisted principles of freedom and equality at their convenience: promoting them in the South, while effectively abandoning them in the West.

Source: The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story by Elliott West

Washington

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Nonexistent

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 0 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Washington’s standards is effectively nonexistent. The Washington State Department of Education adopted the K–12 Social Studies Learning Standards in 2019. The Learning Standards were revised to “align with the College, Career, and Civic Readiness (C3) standards developed in partnership with the National Council for the Social Studies.”

Washington is a local-control state so it is up to districts to create and implement curriculum.

Middle School

The grade 8 social studies course on U.S. history and government spans 1763 to 1877. The standards mention Reconstruction as an historical period that students should know but there are no specific examples or guiding questions related to Reconstruction.

The standards include two sample guiding questions related to slavery and the Civil War that may allow for a discussion of Reconstruction:

What major developments in industry deepened sectionalism before and after the Civil War?

How are the historical events in the United States’ past linked to its present? What is the enduring legacy of marginalization of Native Americans, people of color, and of slavery?

High School

The suggested high school courses in Washington are World History (1450 to Present), U.S. History & Government (primarily 20th and 21st centuries), and Contemporary World Problems & Civics. The U.S. History course might cover Reconstruction at the very beginning, but the chronology is not specific. None of the standards for the high school courses mentions Reconstruction.

Because Washington’s standards provide so little information about whether and how districts and schools should teach Reconstruction, we chose to investigate curricula at the district level. The Local Snapshot below is not meant as a judgment of the district’s approach to Reconstruction. It was chosen largely at random and is not factored into the grade the state standards receive. The brief analysis of district-level curricula that follows is intended to simply provide a snapshot into how state standards, or lack thereof, can shape Reconstruction pedagogy in the classroom.

Local Snapshot

Reconstruction is covered in Spokane Public Schools in a grade 8 “American Studies” course and in two high school courses ,“Gateway to U.S. History” and “U.S. History.” It is the last topic covered in the grade 8 course, as students “study causes, events, and effects of the Civil War and Reconstruction, especially where social, political, and economic elements are concerned.” Both high school courses begin with Reconstruction and describe the unit in identical language: “Students then briefly study Reconstruction before getting into a deeper study of the Post-Reconstruction period, chronologically analyzing American history from Reconstruction through the War on Terror.”

In 2020, Spokane Public Schools approved a high school U.S. history course that spans 1877 to the present. The curriculum of the course will focus on a more inclusive perspective on U.S. history including centering the histories of marginalized groups.

Educator Experiences

Many Washington teachers are making an effort to deepen learning on Reconstruction, but educators who responded to our survey noted that most teachers are not. A high school teacher in Renton explained that they chose to prioritize Reconstruction because it was “one of the most progressive eras in our history, and many students have no idea what took place.” A middle school teacher chose “to spend a good amount of time on Reconstruction in my class.” Yet they noted that “this is not typical when I talk with other teachers in my school and district.”

Teachers who want to center Reconstruction in their classrooms often have to seek out resources on their own. One middle school teacher who responded to our survey said “there is not much support for teaching materials beyond the textbook. The textbook does not give a complete view of many historical events.”

Several teachers from Washington wrote about their experiences using the Zinn Education Project’s “Reconstructing the South: A Role Play” lesson. Danielle Canfield said the role play lesson “was a great way to re-emphasize how history is not just about the past, but also about the present and the future. . .students were able to begin talking about privilege and how land and wealth are connected to opportunities — they were able to discuss generational impacts still felt today that began with Reconstruction. It was powerful to see so many students connect this historical time period to ongoing issues that affect us all.”

Several teachers who responded to our survey cited the benefits of flexibility and autonomy in their determining curriculum. “We are pretty free to teach what and how we want to, and there is a push to center social justice and anti-racism in our curriculum, and Reconstruction ties directly to this work,” said one high school teacher. Still, teachers who responded to our survey noted that pacing and time constraints were major obstacles to teaching Reconstruction.

Assessment

The Reconstruction standards in Washington are effectively nonexistent and do not engage with Reconstruction beyond mentioning that it is a historical period that should be taught. Two guiding questions on slavery and the Civil War offer opportunities to discuss, Reconstruction. However, one of these questions frames “developments in industry” as the driver of deepening sectionalism, and this phrasing is extremely problematic. Among those “developments in industry” is presumably chattel slavery. However, framing slavery as an industrial development conceals and devalues the lives of those enslaved. Slavery did not cause the Civil War merely because it shaped sectional industrial developments. The actions of enslaved people to escape, resist, and claim freedom, which contributed to the abolitionist and free soil movements, were significant factors in the deepening sectionalism that eventually led to the war. Those narratives cannot easily be included in a story of “developments in industry.”

In Washington, it is entirely up to districts and teachers to decide whether and how to teach Reconstruction. Some teachers, schools, and districts may go beyond the standards, as in the case of Spokane’s new U.S. history course that promises to cover more diverse perspectives. That new program, however, merely highlights how little coverage of Reconstruction schools are currently encouraged to provide.

Without guidance around key Reconstruction-era history, many students will not learn about the intensification of white supremacy, the Black Codes, the KKK, debates over who would control land and labor, and Black agency and political organizing. Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In January 2022, Republican lawmakers introduced HB1807, a bill that would prohibit schools from requiring teachers to participate in professional development that teaches about systemic racism or sexism in the United States. They also introduced HB1886 to ban “critical race theory” from classrooms. Both bills died in committee, but their introduction is still troubling. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.