Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle

How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction

By Ana Rosado, Gideon Cohn-Postar, and Mimi Eisen

With the Zinn Education Project team

© 2022 Zinn Education Project

Artwork by Aaron Douglas

—Kidada E. Williams

Introduction

In 2016, the National Park Service described Reconstruction as “one of the most complicated, poorly understood, and significant periods in American history.”1 Kate Masur and Gregory Downs, “Introduction” in The Reconstruction Era: Official National Park Service Handbook ed. Robert K. Sutton and John A. Latschar (Fort Washington: Eastern National Publishing, 2016), 19.

Even as ongoing crises with obvious links to the Reconstruction era continue to reinforce its significance today, most people living in the United States know shockingly little about the policies, people, conflicts, and ideas that shaped Reconstruction and its aftermath.

Reconstruction was a moment of profound hope and devastating loss. Four million formerly enslaved people gained freedom and made strong claims on political, economic, and social equality. However, this “new birth of freedom” for African Americans was met with a white supremacist backlash. With bullets, nooses, laws, and threats, politicians and vigilantes worked to overturn the radical promise of Reconstruction and end multiracial democracy in the South for a century.

A depiction of white terror in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1866, as white supremacists burned down Black churches, homes, and schools. Source: Tennessee Virtual Archive

Historical connections to Reconstruction surround us today: the Movement for Black Lives, rising white supremacist violence, virulent voter suppression, multiracial movements to address policing and labor, political efforts to ban accurate history from classrooms, and racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates. The attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, symbolized by a Confederate flag waving in the Capitol, attempted to overturn the 2020 election results; in the 1870s, white supremacist terrorists throughout the South successfully defeated democracy and equality for more than a generation.

As these recent events have reinforced Reconstruction’s relevance, they have also heightened the need to interrogate why it remains so poorly understood. This report represents a comprehensive effort by the Zinn Education Project to understand Reconstruction’s place in state social studies standards across the United States, examine the nature and extent of the barriers to teaching effective Reconstruction history, and make focused recommendations for improvement.

This report asks four fundamental questions:

Do state social studies educational standards for K–12 schools recommend or require students to learn about Reconstruction?

Is the content that state standards recommend or require on Reconstruction historically accurate and reflective of modern scholarship?

What would an ideal set of historically accurate state standards on Reconstruction look like?

What are some efforts underway to give the Reconstruction era the time and perspective it deserves?

Before answering those questions, we must first understand what Reconstruction was, why people in the United States often struggle to remember it, and why it remains so relevant today.

| Teachers and students at a Freedmen's School in New Bern, North Carolina, c. 1868. Source: National Museum of African American History & Culture |

Reconstruction Defined

Knowledge of Reconstruction is critical for comprehending both the broad sweep of U.S. history and the political debates and social realities that still divide us. For the past century and a half, people have fought over the meaning — the historical memory — of Reconstruction. Arguments over when Reconstruction began and ended, who it helped and hurt, and whether it failed or was defeated all carry critical implications for ongoing struggles for equality and justice in the United States.

Reconstruction was a social, economic, and political revolution. The process began during the Civil War, as enslaved people broke their bonds, escaped to freedom, and joined the U.S. Army and Navy to complete the destruction of the Confederacy. Newly emancipated African Americans who sought to win a semblance of autonomy and self-determination guided the course of Reconstruction and pushed to expand the frontiers of civil and political equality. Yet, faced with Black political and economic advances, a white supremacist counterrevolution succeeded in destroying many of these fragile advances. White supremacists violently suppressed Black voting and sought to reinstitute the racial hierarchy in the South that emancipation had unsettled.

In the South, Reconstruction is largely a story of Black bravery, activism, and grassroots advocacy undermined by political infighting, inconsistent white allies, and virulent white supremacist terrorism. Against difficult odds, many formerly enslaved people were able to carve out a semblance of economic and political independence, but many more were denied the opportunity to own land or freely negotiate work contracts.

Black people organized to fulfill freedom’s promise. They struggled to set the terms of their own labor and advocated for state-funded public education, access to land, the right to vote, and the right to serve on juries. They participated in state constitutional and political conventions, built churches and mutual aid organizations, and ran for and held political office at every possible level of government. Black people also reconstituted their communities: searching for, and sometimes successfully reuniting with, family stolen away in slavery; formalizing marriages; and otherwise living with and near their loved ones. They nurtured these communities with joy and entertainment, gathering at concerts, picnics, and other recreational outings. They cultivated a flowering of Black culture through creative pursuits that included art, music, dance, and literature.

Many white Southerners wanted to undo the progress of Reconstruction and reestablish the antebellum social order rooted in white social, political, and economic supremacy. There were everyday forms of terror and violence perpetrated by individuals who coerced, beat, raped, and murdered Black men and women. There were also collective forms of violence from white mobs and terrorist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, White Leagues, and the Knights of the White Camelia. Much of the violence was politically motivated and specifically targeted Republican voters, organizers, and politicians, and Black people who were prominent in their communities.

To give just one example, on election day in Mobile, Alabama, in November 1874, a white supremacist mob opened fire on Black voters when they attempted to approach the polls. One man was killed and four wounded. The “organized mob” then rushed to the homes of prominent Black men, including religious leaders, with the goal of killing them “for the conspicuous part they had taken for the Republicans during the day.” Those who made it out in time “slept out” in the woods to avoid the murderous mob until after election day.2 Alabaman by Birth, “Elections in the South,” Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago, IL), Nov. 11, 1874, 2.

Black people resisted this violence and sometimes mounted armed resistance, but the combination of vigilante violence, state and federal refusal to defend Black rights, and widespread disenfranchisement was impossible to overcome. Many victims of pre-election threats and violence were forced to flee their homes, abandoning their hard-won economic freedom and political rights to preserve their very lives.

Reconstruction did not reshape just the Southern states. In the West, the legal and economic transformations of Reconstruction profoundly shaped the lives of Native peoples and immigrants from China, often for the worse. As the United States remade itself, Republicans centered a vision of an expanding U.S. empire rooted in the dispossession and domination of Native nations. The Civil War had been waged in large part over the future of the West, and while the triumphant Republican vision for the West did not include slavery, it also did not include Native people. The Homestead and Transcontinental Railroad Acts, passed during the war, provided additional impetus to the displacement and murder of Native peoples of the West.

In California, white wage workers created a political movement to restrict Chinese Americans’ economic and political rights. This movement grew into a popular state party and a national bipartisan coalition that employed a warped definition of the 13th Amendment’s ban on slavery to outlaw most Chinese immigration in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. In New Mexico and Arizona territories, large land owners defied federal enforcement of the 13th Amendment outright, continuing to hold kidnapped Native Americans in bondage for decades after the end of the Civil War.3 Stacey L. Smith, "Emancipating Peons, Excluding Coolies: Reconstructing Coercion in the American West," in The World the Civil War Made, ed. Gregory P. Downs and Kate Masur, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 46-75.

At the level of federal law, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, often called the Reconstruction Amendments, fundamentally transformed the nature of citizenship and the powers of the federal government itself. They outlawed slavery, established birthright citizenship, demanded equal protection of the laws and due process of law for all people, and banned racial discrimination in the right to vote. The amendments explicitly gave Congress the power to enforce these principles. The Reconstruction era was, as historian Eric Foner put it, the nation’s second founding. The constitutional changes enacted during this era created a framework that, nearly a century later, Americans used to dismantle legalized white supremacy in the South. Yet, soon after their enactment, the Supreme Court interpreted the amendments extremely narrowly and Congress retreated from its commitment to using them to protect Black people and democracy itself from white supremacist terrorism.

Portrait of the first Black U.S. congressmen, who all took office during Reconstruction and represented Southern constituents. Source: Library of Congress

The temporary ascendancy of Black political power in many localities rested on both federal and local enforcement of these amendments. With federal officials unwilling or unable to enforce the new amendments (and the federal statutes associated with them), white Southerners denied African Americans the economic rights and resources required for tangible mobility and independence. They took back political power using violence, coercion, and fraud. The political and legal advances made by African Americans could not hold. The United States largely returned to a society governed by hierarchies that placed white men at the top. As political scientist Rogers Smith detailed, in the decades that followed the destruction of Reconstruction, reactionary white people encoded gender and racial hierarchies “in a staggering array of new laws governing naturalization, immigration, deportation, voting rights, electoral institutions, judicial procedures, and economic rights.”4Rogers M. Smith, "Beyond Tocqueville, Myrdal, and Hartz: The Multiple Traditions in America," The American Political Science Review 87, no. 3 (1993): 549-66. Accessed June 9, 2021. doi:10.2307/2938735.

But, as Smith noted, white supremacists could erase the advances of Reconstruction “only partially.”5Smith, "Beyond Tocqueville, Myrdal, and Hartz.” The Reconstruction Amendments remained part of the Constitution, eroded by obscene judicial interpretation and political neglect, but ready for reinvigoration in a new century. Black people’s collective memories of their economic and political power during Reconstruction, though forgotten and erased by most of white America, remained potent reminders to them of what mass political movements and grassroots organizing could accomplish. Present, too, in the collective memories of many Black people in the United States was the knowledge (and continued firsthand experience) of the violent lengths to which white supremacists would go in efforts to defend their unequal privileges.

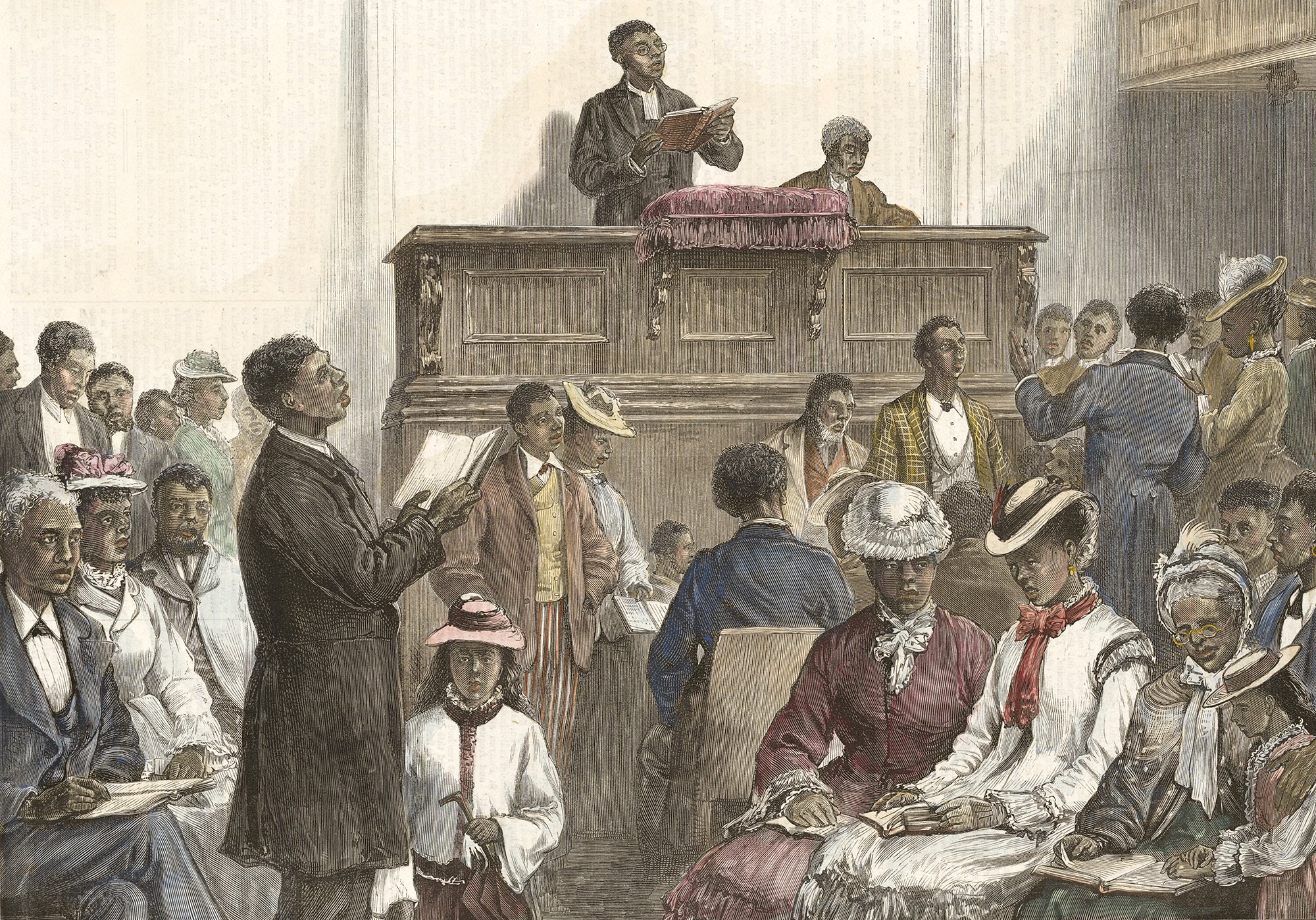

| A depiction of a Black congregation in Washington, D.C., in 1876. Source: National Museum of African American History & Culture |

Why Is It Poorly Understood?

Most people in the United States know very little about Reconstruction. What they do know is often untrue. That’s not accidental. As the great scholar W. E. B. Du Bois said, “one cannot study Reconstruction without first frankly facing the facts of universal lying.”6W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1935), 347.

The “Dunning School,” based at Columbia University and influenced by the research of historian William A. Dunning, dominated white scholarship on Reconstruction for the majority of the 20th century. This school of thought portrayed Reconstruction as a period of intense political corruption where “ignorant” Black people were manipulated by dishonest Northern “carpetbaggers,” and Southern “scalawags.”7Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877 (New York: Harpercollins Publishers, 1988), xvii. Dunning infused his writing with racist interpretations of the period under the guise of historical empiricism and objectivity. As such, Dunning and his students lent academic credibility to what were actually white supremacist distortions of the Reconstruction era. The Dunning School’s impact was profound and reached even into popular culture. D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, the racist 1915 film that depicted Black people as monstrous rapists and the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic organization created to “restore” the South to former glory, was in part based on a Dunning School interpretation of Reconstruction. The film contained title cards with quotes from Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s book, A History of the American People, which made similar white supremacist observations and presented them as facts.

Efforts by Black scholars to condemn the Dunning School, such as W. E. B. Du Bois’s seminal text Black Reconstruction in America, were largely ignored by white scholars until the Black freedom movement of the 20th century created a climate in which professional historians took another look at the period. In the 1950s and '60s, academic historians began debunking the Dunning myths about Reconstruction. Historians have since thoroughly discredited the racist scholarship of the Dunning School and reframed Reconstruction as a time of radical social and political progress that was halted and rolled back by white supremacist violence.8Foner, Reconstruction, xx. They have also drawn from Du Bois’s class analysis of white supremacy, acknowledging how white elites deliberately worked to keep Black and white working-class people from uniting across racial lines and, overall, sought to disempower U.S. laborers. Since the 1960s, historians have enriched and complicated our understanding of Reconstruction in countless ways. This process of discovery and reinterpretation continues today, yet few of these insights have made their way into state social studies standards.

What most students learn in school about Reconstruction is decades behind the scholarly consensus. Historian Eric Foner said, “for no other period of American history does so wide a gap exist between current scholarship and popular historical understanding, which, judging from references to Reconstruction in recent newspaper articles, films, popular books, and in public monuments across the country, still bears the mark of the old Dunning School.”9Eric Foner, “Epilogue” in The Reconstruction Era: Official National Park Service Handbook, ed. Robert K. Sutton and John A. Latschar (Fort Washington: Eastern National Publishing, 2016), 179. Far too many people in the United States still do not understand the history of Reconstruction. Based on our analysis of state educational standards, our national survey of teachers, and our assessment of a sample of district curricula across the country, incorrect and often racist approaches to teaching Reconstruction still define the standards and curricula of many states.

From a lithograph entitled, “The Shackle Broken—By the Genius of Freedom”: a vignette commemorating an 1874 speech on civil rights delivered by Congressman Robert B. Elliott of South Carolina. Source: National Portrait Gallery

The Relevance of Reconstruction

Reconstruction touches nearly every element of modern U.S. life. The legacies of the era shape U.S. government, politics, economics, settlement patterns, and much else besides. In the past year in particular, the legacies of Reconstruction have assumed newfound significance in the ongoing battles over the nature of U.S. democracy, police brutality, and the deadly COVID-19 pandemic.

Reconstruction offers critical context for the racial disparities in COVID-19-related fatalities. As historian Jim Downs explained, the high death toll in the United States among Black people from COVID echoes the destructive outbreak of smallpox among formerly enslaved people during the Civil War that killed uncounted thousands. Notably, smallpox continued to ravage Black communities for decades, long after white authorities had declared the epidemic at an end. During the nationwide racial justice protests in the summer of 2020, many activists described struggling against the twin epidemics of COVID and white supremacy, a formulation that would have been readily recognized by newly freed people struggling against smallpox and the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction.

One of the most notable connections between our current political moment and Reconstruction is the use of Reconstruction-era laws to respond to white supremacist attacks on U.S. democracy. In February 2021, Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) filed a federal lawsuit against former Pres. Donald Trump and others who encouraged or participated in the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol for violating the Enforcement Act of 1871. Congress passed this law, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, to counter the violent attacks on multiracial Reconstruction governments and protect Black people from white supremacist terrorism during Reconstruction. In June 2021, a coalition of civil rights organizations also invoked the Ku Klux Klan Act in lawsuits against Trump supporters who attacked a Democratic campaign bus in Texas, along with the law enforcement officials who allowed the attack to take place.

As a growing conservative movement in state legislatures and school boards has sought to restrict education that foregrounds the history of white supremacy, the work to change the narrative and understand the relevance of this era becomes both harder and more important.

Republican lawmakers in more than two dozen states have introduced legislation to “restrict how teachers can discuss racism, sexism, and other social issues.” Reconstruction, because of its centrality to the history of race in the United States, could be particularly affected by bans on teaching “controversial” topics. Discouraging or banning the teaching of racism, inequality, and white supremacy will make it impossible for students to learn the history of Reconstruction — and its legacies in the contemporary moment. The stakes could not be higher. As one middle school history teacher in Louisiana explained, “It’s impossible to understand the rest of the history of the United States without an understanding of Reconstruction.”

From a lithograph entitled, “The Shackle Broken—By the Genius of Freedom”: a vignette celebrating African Americans' rights to fair labor and land ownership. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Focus and Methodology

This report is designed as a resource for those resisting the current movement at local and national levels to suppress truthful teaching. We assess the state standards that govern the teaching of Reconstruction in every state and Washington, D.C.

Our findings, explained in more detail below, indicate that schools are failing to teach a sufficiently complex and comprehensive history of Reconstruction. We analyzed state standards, district-level social studies curricula, course requirements, frameworks, and support for teachers in each state from 2019 to 2021. We also surveyed elementary, middle, and high school teachers across the country and followed up with individual teachers and education professionals to learn more about how they approach the topic.

Each state summary includes:

A vignette of Reconstruction history in that state.

A brief summary and analysis of the relevant state standards on Reconstruction at each grade level it is taught.

We assess coverage of Reconstruction in each state’s standards as: nonexistent, partial, or extensive.

We assess content and grade standards on a scale of 1–10 in applying the Zinn Education Project standards rubric, described below.

In “local control” states where state educational standards are broad and districts have a great deal of control over what topics are covered, we also analyzed the social studies curricula of one to three school districts. These “Local Snapshots” are not intended as a critical judgment of the chosen districts’ approach to Reconstruction. They were chosen largely at random and are not factored into the grade the state standards receive. They are intended merely to provide a snapshot into how Reconstruction is covered in district curricula when states do not mandate specific content standards.

Our analysis of teacher responses from the state to a survey gathering classroom experiences teaching Reconstruction.

Our overall assessment of the state’s educational standards on Reconstruction.

Note: Our analysis in this report is limited to Reconstruction, but our review of state standards yielded troubling framings for additional areas and eras of U.S. history. Language such as “unsettled territories” and “Westward expansion,” among others, suggest endorsements of imperialism and other reprehensible policies and ideologies. “Unsettled territories,” for instance, disregards the Indigenous people who had already settled and built communities in these regions and excuses white settler invasions and occupations. We largely refrain from addressing these terms as cited directly in the report, given its focus, but do not condone their usage and implications.

Sharecropper by Elizabeth Catlett, 1952. Source: Art Institute Chicago

What We Believe About Standards

This report grows out of the Zinn Education Project’s Teach Reconstruction campaign, which seeks to address the dearth of curricular and pedagogical attention to Reconstruction compared to other formative moments in U.S. history (the Civil War or the Civil Rights Movement, for example). Although this report uses state social studies standards to discuss the limitations of how Reconstruction shows up in K–12 curricula and classrooms, we want to be clear that changing standards is not our primary purpose. Indeed, it is fair to say that we are working toward a vision of education that might very well make standards (as we currently understand them) obsolete. Instead, our hope is to motivate readers to advocate for more attention to Reconstruction in K–12 curricula and classrooms; standards are merely one vehicle for that kind of advocacy.

Standards and the Politics of Knowledge

The standardization of knowledge is a political project that is much broader than what we describe in this report; the project implicates universities, the publishing industry, the textbook industry, media, policy makers, and more. Through the production of standards, some narratives become normalized, glorified, and legitimated while others are suppressed and erased. It matters who holds power in these settings. For example, as mentioned above, the standard Dunning School narrative, which laid Reconstruction’s “failure” at the feet of “inept freedpeople” and their “corrupt allies,” was ascendent in textbooks and classrooms until the 1960s. In his classic 1935 work, Black Reconstruction in America, W. E. B. Du Bois critiqued “the propaganda of history,” and described how the powerful exerted themselves to silence his anti-racist account of Reconstruction. Du Bois explained:

| The editors of the fourteenth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica asked me for an article on the history of the American Negro. From my manuscript they cut out all my references to Reconstruction. I insisted on including the following statement: “White historians have ascribed the faults and failures of Reconstruction to Negro ignorance and corruption. But the Negro insists that it was Negro loyalty and the Negro vote alone that restored the South to the Union; established the new democracy, both for white and black, and instituted public schools.” The editor refused to print [it]...I was not satisfied and refused to allow the article to appear. |

In spite of Du Bois’s stature — he was the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard — he was also a Black man engaged in political activism opposing white supremacy, not only in historical scholarship but also in society. The gatekeepers at the Encyclopedia Britannica opted for propaganda rather than history and called it knowledge. We view state social studies standards through a Du Boisian lens. That is, we believe they are a reflection of power relations in society; they are “the official” history, the version of the past that is currently endorsed by those in seats of power. As such, they have been tools for reinforcing settler colonialism, white supremacy, sexism, and classism in the curriculum — and a site of resistance for those seeking to challenge those oppressive systems.

Standards and Testing

It is also important to note that the movement for standards has historically been tied to the push toward greater testing, a push we oppose. Standards have been used as a rationale for tests and the results of tests used as a rationale for more standards. But while standards have proven a sometimes fertile ground for struggle (as in the ethnic studies example below), testing cannot be redeemed. Our colleagues at Rethinking Schools, Wayne Au and Stan Karp, have written extensively on the damage wrought by testing, which “strangles curriculum, narrows the range of what is taught, and impoverishes the school experience.” Karp continues:

| In recent decades, a sprawling, suffocating — and highly profitable — apparatus of standardized testing has replaced teacher-designed assessments with a “data-driven” mania that is the engine of test-and-punish reform. Data from deeply flawed multiple-choice tests, commercially designed and often scored by machines, is used by policy makers far removed from classrooms to make decisions about whether students get promoted or graduate, whether teachers keep their jobs, even whether whole schools are closed. |

Standardized testing has also been a tool of white supremacy. As Au explains,

| high-stakes tests are not race-neutral tools capable of promoting racial equality. At their origins more than 100 years ago, standardized tests were used as weapons against communities of color, immigrants, and the poor. Because they were presumed to be objective, test results were used to “prove” that whites, the rich, and the U.S.-born were biologically more intelligent than nonwhites, the poor, and immigrants. In turn, the tests provided backing to early concepts of aptitude and IQ, which were then used to justify the race, class, and cultural inequalities of the time. |

While recent proponents of testing promise it will help “close the achievement gap,” the eugenics origins of standardized testing are inescapable. Since their inception, these tests have exacerbated inequality, not diminished it. Our call for better standards around the teaching of Reconstruction is not a call for more testing. Period.

The Struggle Over Standards

For all their limitations, standards are not fixed. They are always undergoing transformation that is itself often a consequence of struggle and resistance by teachers, students, parents, and community members. Reading through our report, one finds ample evidence of this ongoing process. We note that Arizona adopted new standards in 2018, that Virginia is in a revision process that should be complete in 2022, and Washington State has been working from its newest version of standards since 2019 — a version that replaced those adopted in 2008. Recently, movements for ethnic studies and to teach about tribal sovereignty have made standards a vehicle for combating curricular white supremacy and colonialism. As of Jan. 2022, at least 12 states have adopted some form of ethnic studies standards. These versions of state social studies standards reflect ongoing debates about how the past should be interpreted and transmitted through schooling. Unfortunately, too often this lively, dynamic story-behind-the-story is left out of the uses to which standards are put. Standards are delivered to educators in cold, bureaucratic documents along with the mandate to “align” their curricula, and are almost always invisible to the students who are their purported beneficiaries. Rarely do the standards themselves make it into the curriculum for discussion and debate.

Standards and Curriculum

What does make it into the curriculum? Unfortunately, standards won’t help us fully and accurately answer that question. There is an enormous gap between the bureaucracy of state standards and the living, breathing, dynamic organism that is a classroom. Some teachers hew closely to the standards; some teachers do not. Some schools encourage their faculty to “teach outside the textbook” while others do not. Two teachers in the same state, teaching to the same standard, can spend dramatically different amounts of time on the same topic. In this report, we glimpse only a tiny fraction of what teachers are actually doing.

We do, however, believe that standards often help shape teachers’ curricular choices and that without better Reconstruction standards, teachers are more likely to defer to the version of that era found in textbooks and corporate curricula. This version too often emphasizes Reconstruction’s “failure,” spends more space on white “backlash” than on the contributions of formerly enslaved people and their allies, and centers debates between Congress and the president rather than the demands for justice led by everyday people, especially Black people.

Our hopes for the Zinn Education Project’s Recommended Standards rest upon our belief that given time, quality resources, and meaningful professional development, teachers can and will build relevant, engaging, and rigorous curriculum best suited to the particularities of their own context. These standards will not alone make that happen. But they do, we believe, qualify as “quality resources” that can help frame professional conversations, curricular investigations, and lesson and unit planning.

What We Are Not Saying About Standards

-

There are many struggles over schools more important than what is or is not in the state standards with regard to Reconstruction. School funding, for example, which is chronically inadequate, would solve many of the obstacles teachers told us stood in the way of teaching Reconstruction with the care and attention it deserves. Again and again educators told us how scarcity impacted their curricula. They reported not having enough space in the scope and sequence of their course to include Reconstruction, not enough time in their work days for the construction of high-quality curricula, and not enough opportunities to learn about Reconstruction through professional development. Another critically important struggle is around schools’ commitment to anti-racist pedagogy and practice. When educators prioritize engaging children in a critique of the roots of inequality — and teach about efforts to build a more just world — Reconstruction becomes an obvious site of inquiry. Finally, as the pandemic demonstrated so painfully, schools are far more than just institutions that impart knowledge and skills to students. They are vital to the health and safety of communities. No one can learn history — or put it to good use — if they are hungry or sick. First and foremost, schools must be humane institutions of care.

-

We know that there are educators in every corner of this country who are working everyday to design and teach powerful lessons that spark students’ curiosity and democratic capacities — no matter their state standards.

-

We know that good teaching requires much more than a good set of content standards. Teachers must demand the opportunities to create curriculum with one another and to demonstrate — and learn from — exemplary strategies. Standards may or may not play a role in this process of grassroots teacher education, but teachers must use their unions as well as their professional and activist organizations to keep curriculum vital. And this ongoing process must receive robust funding.

-

It is unfortunate that the word “accountability” has been hijacked by proponents of testing to mask practices that sort, stratify, and punish children and schools. We oppose that kind of accountability. We do, however, invite educators to imagine and build learning and activist communities in which they might articulate a set of values to which they do want to be held accountable: truth, justice, care, transformation, etc. In such a setting, accountability to history and to our collective past would be welcome.

IN SUMMARY

We view this report as part of the larger conversation happening in this country over our shared history. From fights over the status of Confederate monuments, to sometimes furious, sometimes glorifying pronouncements about the New York Times 1619 Project, from the rash of laws seeking to ban the teaching of race and power sweeping the nation to popular culture’s treatment of everything from slavery to racist massacres to the Black Panther Party, we are in the midst of a national struggle over how we remember slavery and its legacies. This struggle makes clear that the historical narratives we internalize about our nation, ourselves, our neighbors, and the people on the other side of the town shape our actions in the present and our vision of the future. The history of the Reconstruction era belongs in this national conversation. Although improving state social studies standards will not alone accomplish this task, it is one point of entry worthy of our time and attention.

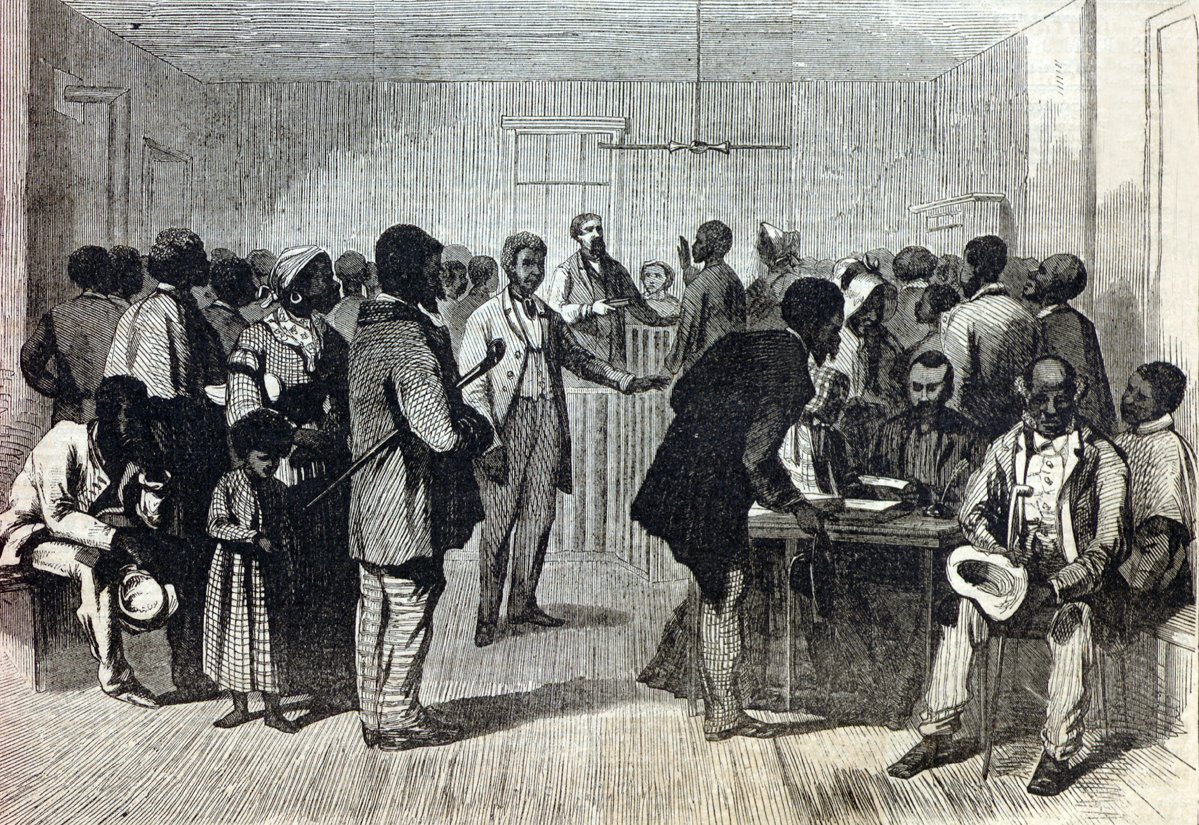

| A depiction of Freedmen's Bureau offices in Richmond, Virginia, in 1866. Source: Dickinson College |

Rubric and Recommended Standards

The Zinn Education Project, in collaboration with scholars and teachers, created and rooted our assessment of the state of Reconstruction education in the set of teaching and learning standards below.

The foundational premise of any set of teaching and learning standards for the Reconstruction era should be Black people’s agency, highlighting both what Black people did (to end slavery, engage in politics, build institutions, etc.) and what goals, beliefs, and motivations undergirded those actions. Descriptions of the violent backlash to Reconstruction should emphasize how white supremacist ideology drove the effort to overturn multiracial democracy in the South and shaped the political and economic development of the entire nation after the Civil War.

It is our hope that states and districts will adopt the following guidelines for their own educational standards, curricula, and professional development. In so doing, they will be better equipped to teach students the true history of Reconstruction, helping students understand its significance and make connections to the present day. And they will empower teachers to educate their students and themselves about ongoing Reconstruction scholarship.

In schools throughout the United States, students should:

Examine what Reconstruction reveals about the meaning of freedom to Black people.

For example, lessons should examine how formerly enslaved people exercised autonomy over self, family/kin, community; organized and mobilized around issues of land, labor, production, education, and worship; cultivated joy and creativity; sought the civil and political rights most critical to their freedom; and conceived of that freedom through traditions of resistance formed long before emancipation.

Know that control of land was of paramount importance to formerly enslaved people during Reconstruction, but widespread land reform and Black land ownership were systematically denied by federal and state governments.

For example, students should examine the Savannah Colloquy and Special Field Order No. 15, the Homestead Act vs. Southern Homestead Act, Pres. Johnson’s “restoration” of land to Confederates, and the rise of state and local policies designed to immiserate and confine Black people.

Know that the struggle by freedpeople to control their own labor during Reconstruction was a source of conflict between freedpeople and economic elites, North and South.

For example, students should examine the Freedmen’s Bureau’s role in overseeing labor contracts between the formerly enslaved and white land owners, Northern elites’ desire to restore the Southern plantation economy, and the racial politics of labor organizing, North and South.

Examine the Freedmen’s Bureau to determine what it reveals about the needs and desires of freedpeople at the end of the war, its successes and failures, and how and why it was dismantled.

For example, students should examine how the Freedmen’s Bureau — formally named the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands — worked to secure food and medical care for freedpeople, reunite loved ones separated in slavery, establish school systems, redistribute land; how white resistance to these aims and lack of funding impeded and overwhelmed its efforts; and how white supremacists across regions targeted agents and pressured Congress to disband it.

Examine the modes of mass political participation of Black people during Reconstruction.

For example, students should investigate the Union Leagues, state constitutional and political conventions, voter registration and education campaigns, press outlets, self-defense and self-help organizations, and schools and churches.

Examine the advances for democracy and racial justice made due to the mass political participation by Black people during Reconstruction.

For example, students should investigate African American lawmakers and officeholders elected at all levels of government; passage of laws at the state level providing tax-funded public schools, fair labor contracts, universal male suffrage, the right to divorce, the right of Black people to hold office and serve on juries; support for and mobilization around Radical Republican efforts in Congress: Reconstruction Acts, Enforcement Acts, and the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Know that white supremacists used terrorism and fraud to stall and reverse many of the significant advances made by Black people and their allies during Reconstruction, and shaped the politics, policies, and outcomes of the era.

For example, students should analyze different manifestations of racism in the Democratic and Republican parties, South and North, and in labor relations, South and North; how Black institutions and symbols of Black achievement were undermined with racist terror and violence; and how violence (vigilantes, the Ku Klux Klan) functioned to achieve the white supremacist goals of the Southern Democratic Party and the rise of Jim Crow apartheid.

Learn how elites in the North and the Republican Party prioritized their own economic interests by retracting support for the federal government’s role in protecting the advances made by Black people and their allies during Reconstruction.

For example, students should analyze how Northern industrialists successfully extended their dominance into the South — including Northern railroads acquiring massive tracts of public and Indigenous land — which shaped their interest in maintaining status quo labor relations; and how the 1873 economic depression fueled labor activism and strikes, incentivizing Northern industrialists to join Southern “redeemers” in a politics rooted in the fear of a revolt from below.

Investigate the legacy of the crushing of Reconstruction’s promise in their own lives and the current historical moment.

For example, students should examine the United States’ failure to award reparations for slavery; the failure of the federal government to endorse and support the most transformative promises of Reconstruction: land reform, universal suffrage, and civil rights; and the persistence of Jim Crow racism at all levels of society (policing and prisons, disparities in health, wealth, housing, employment, and education).

Investigate positive legacies of the Reconstruction era in their own lives and the current historical moment.

For example, students should examine Reconstruction-era schools and churches; the rich tradition of Black politics; the 14th and 15th Amendments, which continue to be the basis for expansion of and defense of civil rights; and Reconstruction as a model of grassroots activism and participatory, multiracial democracy.

A family in Savannah, Georgia, c. 1907. Source: Library of Congress

Key Findings

School district standards:

Emphasize a top-down history of Reconstruction focused on government, politics, and policy with little emphasis on ordinary Black people and their organizing strategies.

Most Reconstruction state standards emphasize congressional and presidential debates, politics, and policies. Although this is an important part of the history of Reconstruction, the political narrative all too often leads to emphasizing the actions of white people and normalizing a theory of change that moves inexorably from the top down. State standards sometimes mention Black officeholders, though often not directly by name; instead, standards highlight the phenomenon of Black officeholding.

The top-down approach overshadows Black people’s grassroots political mobilizations and lived experiences. Theron Wilkerson, a Mississippi social studies teacher, noted that “because teachers are often pressured to ‘teach to the test,’ fruitful discussions about Black political, cultural, and economic autonomy, the potential of radical democratic participation, and the destruction of Reconstruction is lost.”

Still promote an inaccurate history of Reconstruction influenced by the Dunning School.

Several states employ terms and emphasize elements of Reconstruction history that echo the discredited Dunning School approach. Notably, Oklahoma, Alabama, and Tennessee, among others, require students to “explain the roles carpetbaggers and scalawags played during Reconstruction.” These terms were used mainly by white Southerners opposed to Reconstruction to denigrate, respectively, Northerners who moved South and Southern whites who sided with Republicans. Although they are important terms to learn, the lack of explanatory context in the standards is troubling. By encouraging students to view the participants of Reconstruction from the rhetorical perspective of opponents of Black civil and political rights, these standards risk perpetuating a flawed and white supremacist history of the era.

The emphasis in many standards and textbooks on evaluating the “successes and failures” of Reconstruction is also partly a legacy of the Dunning School. This distorted scholarship casts Reconstruction as an illegitimate, reckless enterprise that justifiably failed to sustain the rights it granted to formerly enslaved people. The school propagated white resentment toward Black people and their allies during Reconstruction and convoluted framings of “successes and failures.” For most of the 20th century, white supremacists often cited “failure” as an overarching inevitability of Reconstruction and a reason to deny Black people full citizenship in the decades that followed. Nicole Clark, a middle school teacher in Washington, D.C., expressed concern that curricula on Reconstruction still focus “more on failures and white rage than the advancements.”

The “successes and failures” framing often neglects to ask “for whom?” and encourages inaccurate and white supremacist Reconstruction education today. It undercuts the era’s on-the-ground movements, disconnecting the actions of people from the consequences of history. It belies the radical possibilities, unparalleled civil rights progress, and devastating white supremacist terror that are all so characteristic of Reconstruction. It assumes a sense of passivity, often asking students to consider only elites or vague monolithic entities like entire states or bodies of government as primary actors building toward inevitable outcomes. In so doing, this framing separates the genuine achievements of Reconstruction from the coalitions of Black people who made them possible and the racist dismantlers who deliberately rolled them back. An overemphasis on “failures” overshadows the transformative nature of Reconstruction and obscures how white supremacists violently destroyed Reconstruction precisely because of its successes. It invites students to instead view U.S. history through a mythical lens: a gradual, straight line from slavery to a post-racial present, leaving them unaware of Reconstruction’s significance and unprepared to confront the nation’s realities.

Rarely name or contend with white supremacy or white terror.

Only one state, Massachusetts, mentions and directly links white supremacy to the rise of the KKK, the passage of Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, and the end of Reconstruction. Only by grappling with the persistence of white supremacist ideology will students understand why so many white Southerners turned to violence to destroy Black voting, officeholding, and economic independence. Most critically, foregrounding the prevalence and political power of white supremacy will encourage educators to teach their students that Reconstruction did not passively fail, as so many state standards assert, but was actively destroyed.

Do not provide clear and consistent definitions of Reconstruction.

Many standards and textbooks do not actually articulate what Reconstruction was, and some do not even capitalize the term when referring to the period or project itself. Neglecting clear definitions throughout the unit leaves room for warped and white supremacist interpretations of the era’s leading actors and lasting significance. This lack of direction is often exacerbated by unsound instructions written into student activities. For instance, Georgia’s standards task students with comparing and contrasting the goals and outcomes of agencies like the Freedmen’s Bureau with white supremacist terror groups like the KKK, extending a semblance of moral legitimacy to people and causes deserving only condemnation. Coupled with nebulous terminology for the project of Reconstruction, such standards leave students vulnerable to ideological justifications for restoring white supremacy in the South. They do not recognize Reconstruction for what it was: a people-led reckoning with white supremacy and grassroots movement for multiracial democracy that reached every region of the United States.

Limit the significance of Reconstruction to Southern states.

Reconstruction was not merely a Southern story. The Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution fundamentally changed the definition of citizenship throughout the nation. Black activists and white allies fought for civil and political equality throughout the United States, striking down discriminatory laws in the North as well as the South. Although many state standards describe the enfranchisement of Black men in Southern states during the late 1860s, none mentions that it was only the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870 that allowed Black men in most Northern states to vote.

If classroom practice follows state standards, few students outside of the South learn that their states are often full of Reconstruction-era sites and stories. As just one example, Pennsylvania’s education standards barely mention Reconstruction. Teachers who responded to our survey described how they went far beyond the standards to lead discussions of the Reconstruction Amendments, literacy tests, and Black Codes. Yet, none mentioned the dramatic fight for Black civil and political rights in their home state during the Reconstruction era. Pennsylvania is home to a great deal of Reconstruction history, perhaps most notably the story of Octavius Catto, a Philadelphia educational, baseball, and voting rights pioneer who was murdered on election day in 1871. Yet, the state standards, which barely mention Reconstruction at all, do not treat it as an important element of Pennsylvania’s history.

This failure likely has consequences for how much time teachers devote to the topic and how well students engage with it. One middle school teacher in Wisconsin noted that their students struggled to connect to the themes of Reconstruction because they saw “themselves as geographically removed from these events.” Yet, Wisconsin is very much a part of the Reconstruction story. Teachers could introduce their students to the stories of the Republican legislators the state sent to Washington to enact Reconstruction policies, the Black residents of Milwaukee who fought against segregation in the 1880s, and the Native peoples whose legal status was both strengthened and undermined by Reconstruction’s new definitions of citizenship. Telling the story of the history and legacies of Reconstruction in every corner of the country will help teachers make the case to their students that these legacies matter to their lives, no matter where they live.

Do not address the enduring legacies of Reconstruction or make connections to the present day.

We live with the echoes of Reconstruction to this day. The 14th and 15th Amendments continue to be the basis for expansion of and defense of civil and voting rights. Their influence on definitions of citizenship and state protections is so profound that historians have described the era as a Second Founding. Reconstruction also provides a potent model of grassroots activism and multiracial democracy that continues to inspire advocacy and reform.

Teaching the legacies of Reconstruction can carry risks in our politically polarized times. One North Carolina high school teacher said, “by making the connections to more recent times, or discussing the rise of white supremacist groups, there are accusations of indoctrination.” A high school teacher in Washington emphasized that “polarized culture” and “parents not agreeing with teaching real history” imposed serious constraints on the kinds of connections teachers could make between Reconstruction and the present day.

Do not provide sufficient time to cover Reconstruction.

State standards encourage classroom teachers to either rush through Reconstruction or skip it entirely. Kerry Green, a Texas high school teacher, said the problem was primarily due to the “the scope, sequence, and pacing of the standards.” One New Mexico middle school teacher explained that, absent detailed standards, “not enough teachers see the importance of spending more time teaching Reconstruction.” An Illinois middle school teacher affirmed that “Reconstruction is generally the most skipped and summarized” unit in their curriculum.

The placement of Reconstruction as the “halfway point” in U.S. history means that it often falls at the beginning or end of a grade year. Grade 8 history courses are frequently designed to cover the Constitution to Reconstruction (1776–1877, or 1800–1900), a formidable length of time for one year of instruction. High school history courses then typically pick up the narrative from 1877, but in some cases (for example, Arkansas and Utah) grade 9 non-AP U.S. history courses begin in 1890, meaning that Reconstruction can easily fall into a gap and out of the official curriculum. One Vermont high school teacher explained that having Reconstruction begin or end a year meant that students in the same school could learn nothing at all about Reconstruction or spend weeks on the subject, entirely “depending on individual teachers’ priorities and comfort” with the material.

Many instructors feel unprepared to teach Reconstruction.

Teachers who responded to our survey indicated that they had to do a significant amount of self-education to effectively teach Reconstruction in their classrooms. In some cases the vagueness of state standards allowed teachers to create their own innovative Reconstruction curricula. But generally teachers reported needing more support, not less, to improve their teaching of Reconstruction in the classroom. One Texas high school teacher said, “I would really like to see more specific guidance on what to teach about this topic. I feel like it’s so important to get this course right, but also feel like I am not doing an adequate job and have not found enough resources.”

States fail to set suitable standards for Reconstruction.

State standards for teaching Reconstruction are frequently so vague and broad that, as one Oregon middle school teacher explained, “an educator could skip Reconstruction and still technically ‘meet’ the standards.” When state standards do mention specific events and people, they mostly emphasize top-down political developments and prominent white men. Standards rarely mention Black people by name.

A particularly common element in state standards is to ask students, as does Connecticut, to “analyze reasons that the Reconstruction era could be seen as a success and reasons that the Reconstruction era could be seen as a failure.” This success/failure framing is often used as a starting place or a broad lens through which to examine Reconstruction. As mentioned above, this framing is problematic because it obscures both Black people’s agency in the struggle for freedom and white people’s backlash and violent repression. This framing reinforces a Dunning-era narrative in the standards in more than 15 states.

Teachers are concerned that ongoing political efforts to ban “controversial topics” from the classroom may block coverage of Reconstruction.

As of June 13, 2023, at least 44 states have introduced bills, resolutions, or other measures targeting the teaching of certain “controversial topics” in the classroom. Eighteen of these states have enacted bans through legislation or other courses of action. In addition to these statewide policies, in recent months there have been dozens of more local efforts to restrict what young people can be taught about race and racism in the classroom.

As increasing numbers of teachers have committed to teach outside the textbook, these laws and policies attempt to reinstate and indoctrinate young people with white supremacist curricula. Their right-wing authors and supporters claim to target the teaching of “divisive topics,” a shape-shifting term that uses the language of antidiscrimination to both shroud and strengthen a discriminatory status quo. For instance, Louisiana’s “divisive topics” provisions include a ban on the concept “That either the United States of America or the state of Louisiana is fundamentally, institutionally, or systemically racist or sexist.” In other words, it tasks educators with neglecting the very existence of racism and sexism and denying students acknowledgement of the real and present injustices they encounter. An editorial from Rethinking Schools noted, “By banning educators from teaching about these realities, lawmakers seek to deny young people the right to understand — and so effectively act upon — the world they’ve been bequeathed. These bills are an attack on democracy itself.” The same far-right political forces campaigning against accurate and anti-racist curricula have also ushered in waves of voter suppression laws as part of a sweeping attack on democracy.

Although conservative advocates of these antihistory education bills have touted their likely political effects on the 2022 midterm elections, they already threaten to shape classroom instruction. As Rashawn Ray and Alexandra Gibbons noted in a report for the Brookings Institution, these laws could have “a chilling effect on what educators are willing to discuss in the classroom.” Educators and advocates have expressed concerns that the broad language of these bills could compel teachers to shy away from discussing racism in U.S. history. And it is impossible to teach the history of Reconstruction without discussing racism. Moreover, it is impossible to teach about the unequal character of our society today without exploring what happened — and what did not happen — during Reconstruction.

In this environment, it is increasingly important that state social studies standards explicitly discuss Reconstruction. In Oklahoma, the inclusion of the Tulsa Race Massacre in the state social studies standards may preserve the topic in curricula, despite the restrictions of the new state law. Similarly, detailed coverage of Reconstruction in the required standards could provide teachers with a bulwark against spurious accusations that discussing Black activism and advocacy and white supremacist terrorism in the 1860s and ’70s is a banned “controversial topic.”

Five officers of the Women's League in Newport, Rhode Island, c. 1899. Source: Library of Congress

Recommendations

Grounded in the Zinn Education Project Rubric and Recommended Standards, Key Findings, and What We Believe About Standards sections of this report, we suggest several major improvements to state and school district frameworks that would better equip teachers and students to engage with the truth and complexity of Reconstruction in K–12 education.

Provide clear and consistent definitions of Reconstruction.

Standards and curricula must make clear that Reconstruction refers to the post-Civil War, Black-led mass reckoning with U.S. traditions of white supremacy, tenets of citizenship, and conceptions of freedom. Instead, they often approach Reconstruction as a series of names and dates organized around legislative and presidential activities in the period following the war. These names and dates can be important, but prioritizing them over the goals, achievements, and lived experiences of ordinary Black people undermines the true nature of Reconstruction. It was not a neatly bound, easily bookended 12-year period — it was a larger process of creating a more just society from the ground up, and African Americans were central to it. As a term and an undertaking, it should be capitalized and clearly defined from the outset. Without context, the purpose and people of Reconstruction remain ambiguous at best; without capitalization, the term does not formally refer to the historical era. The project of Reconstruction should be articulated clearly and consistently to orient educators and students to the unit and avert misguided interpretations of its leading subjects and lasting significance.

Foreground the meaning of freedom to African Americans and the actions they took to realize it.

The momentum of Reconstruction and the radical promise it held stemmed from grassroots Black organizing. Standards and curricula must center Black people’s efforts to redefine freedom across economic, political, and social realms during and after the Civil War. They should delineate the many ways Black people reconstituted their communities and made advances for multiracial democracy, such as:

Fighting for access to land and fair labor, as well as the rights to vote; sit on juries; hold office; and otherwise participate in political, economic, and legal systems. Many standards and curricula frame Reconstruction from political and legal angles, but typically focus on branches of government, states, and amendments while neglecting the profound actions of ordinary people. Black people’s political mobilization and efforts to secure their own land and labor fundamentally transformed the nature of U.S. citizenship and must be treated accordingly. Their struggle for economic agency under racial capitalism should also be acknowledged outright, as it shaped many disparities in power framed as purely political in nature.

Championing statewide public education, autonomous worship and mutual aid organizations, and affirmation of familial ties. Some standards and curricula mention strides in education as an aim of the Freedmen’s Bureau, but do not adequately acknowledge the revolutionary nature of widely accessible, state-funded public school systems and their origins in Black frameworks for civic life. They should, in fact, prioritize the many ways African Americans asserted their autonomy and nurtured their kin during Reconstruction. Founding Black churches and mutual aid societies, finding loved ones separated in slavery, and formalizing partnerships were all actions rooted in care, justice, and opportunity. These values and efforts have informed movements and institutions for generations since.

Cultivating everyday joy and entertainment, artistic expression, and creative pursuits. Virtually nonexistent in most standards and curricula, and indeed many other outlines or retellings of Reconstruction, is any mention of the ways African Americans expressed their connections to each other, themselves, and the world around them through habitual acts of joy and creativity. Questions of equality during Reconstruction often turn to entitlements like life and liberty, while sidelining the very real, present, everyday pursuit of happiness. Picnics in parks, concerts at churches, and crafts honed at home all exemplify a flowering Black culture grounded in liberation. Against the backdrop of white supremacy, such celebrations of humanity and vitality also signified resilience. They must be introduced as intrinsic to the history of Reconstruction.

Examine the establishment, activities, and legacies of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Many standards and curricula mention the short-lived Freedmen’s Bureau and ask students to evaluate its effectiveness, but all should frame its trajectory as a reflection of both Reconstruction’s revolution and white supremacy’s endurance. The Bureau’s charge to aid millions of formerly enslaved African Americans and hundreds of thousands of poor white people in the decimated South, border states, and the District of Columbia was monumental, unprecedented, and enormously underfunded. As Bureau agents sought to meet the needs and desires of freedpeople — securing medical care, reuniting with loved ones, settling land and labor contracts, establishing school systems — they also found overwhelming resistance from white people united across regions and class lines against Black mobility. Standards and curricula should focus on these coalitions of people working to fulfill or break the promise of freedom. Through that lens, educators and students can better explore the stakes of Reconstruction and know the weight of the Bureau’s successes and failures.

Name and confront white supremacy and white terror.

Reconstruction did not simply end, nor was it simply defeated. As African Americans led a reckoning with racial injustice, white supremacist backlash pervaded most spaces carved out for Black autonomy and deliberately destroyed their progress. Standards and curricula often mention groups like the KKK and legislation like the Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, but they must directly connect their rise and proliferation to the prevalence and socioeconomic power of white supremacy and its role in ending Reconstruction. They should do away with language that suggests Reconstruction ended in passive and inevitable failure, and instead name and explain the white supremacist individuals, organizations, and systems that actively defeated it.

A thorough discussion would trace the resiliency of white supremacy throughout and beyond the South to the racialized nature of capitalism in the United States. Standards and curricula should address, for instance, how many elites in the North and the Republican Party arranged their priorities to suit their evolving financial interests. Northern industrialists, in particular, relied on exploitative labor for ventures like railroads, which they increasingly built on public lands seized in the South. As the 1870s progressed, an economic depression catalyzed widespread labor activism, and Northern and Southern elites unified against the working class. Many people who had once supported the federal government’s involvement in protecting the rights and freedoms of African Americans turned away in short order, effectively abandoning Reconstruction.

Emphasize the significance of Reconstruction throughout the United States.

Although largely framed as a Southern story, Reconstruction reached every region of the nation and met formidable resistance from discriminatory people and policies in the North and to the west. From Black residents nurturing communities and battling segregation on local levels, to legislators working on state and federal Reconstruction laws, to Indigenous peoples navigating expanding and constricting definitions of citizenship, people across the country had a stake in Reconstruction. Standards and curricula must cover grassroots movements for multiracial democracy and justice that arose and extended far beyond the South, redefining freedom and contending with white supremacy in every state. Incorporating these clear, extensive geographical ties both tells a more complete story and brings Reconstruction’s specific relevance to the doorsteps of educators and students who might otherwise dismiss it as someone else’s legacy.

Address the legacies of Reconstruction today.

We regularly encounter issues, policies, and movements steeped in Reconstruction history. Standards and curricula occasionally gesture to the legacies of Reconstruction in the Jim Crow era and 20th-century Civil Rights Movement, but they must do so in ways that implicate people in the present. Lasting foundations for current civil rights laws, renewed attempts to ban truthful teaching from classrooms, enduring racial disparities in healthcare, and persistent struggles over the idea and practice of multiracial democracy all trace back to Reconstruction. Identifying these connections makes clear that white supremacist terror, racial justice movements, and communities of care are all longstanding and consequential components of U.S. history. The legacies of Reconstruction not only affirm that progress is never a straight line, but also provide blueprints for grassroots activism today and radical possibilities for an equitable future.

Adjust curricular timelines to make ample space for Reconstruction.

To implement the above content suggestions, educators and students must have substantial time dedicated to the unit. In many state standards and curricula, Reconstruction appears only in one middle school or high school class, if at all, and is commonly grouped with other periods in ways that eclipse it. For instance, standards and curricula commonly fuse the Civil War and Reconstruction into one unit. While these eras are and should be closely linked, in practice the Civil War occupies far more space in state standards, academic scholarship, and public memory than does Reconstruction. Some classes report spending several weeks on the Civil War, and little to no time on its aftermath in the decade that followed. Many standards and curricula overshadow Reconstruction by design: They may subsume it into a “Civil War” era that extends through 1877 and only gesture to Reconstruction in passing when asking students to assess vague consequences like “damages” or “legacies” of the war.

Even when Reconstruction appears as its own distinct unit, it often falls at the “halfway point” in two-year chronological U.S. history classes, forcing a split and often rushed or altogether forgotten section at the beginning or end of a class curriculum. Reconstruction should be taught extensively at multiple grade levels, and not as a bookend unit at the start or end of the school year. Arranging units to accommodate it more centrally can help mitigate this timing issue. In fact, educators and students may more effectively engage with Reconstruction, and indeed U.S. history more broadly, when not beholden to strict chronology.

A thematic approach may give educators and students space to delve into key patterns and connections throughout history that make the past recognizable and relevant. For instance, a theme centered on voting rights could involve significant time spent examining their legal and social expansion during Reconstruction and evaluating changes and continuities into the present.

Increase professional development for Reconstruction education.

In order to teach Reconstruction effectively, educators must first have the time and resources to learn it themselves. Many teachers report not learning about Reconstruction at all during their own schooling or training, let alone thoroughly enough to build curricula and plan lessons to teach their students about it. Those who do attempt to establish or improve teaching Reconstruction typically do so independently and without tangible institutional support. In many cases, teachers have professional development (PD) days, but that time is often allocated for familiarizing themselves with existing pedagogical frameworks like grading rubrics and school district or state standards. Teaching a topic as pivotal, misunderstood, and suppressed as Reconstruction requires far more dynamic and deliberate PD that encourages teachers to inhabit their roles as both education professionals and lifelong learners.

The strongest PD models take a collaborative, bottom-up approach in which educators meet and learn from each other’s expertise — exploring their practices, working through obstacles, and building curricula together. Classes, workshops, lessons, and activities that support pedagogical reflection and revision should be made readily available and accommodated into educators’ schedules. Schools, districts, and state departments of education should facilitate this high-quality PD with ongoing structural support, like funding study groups dedicated to finding, discussing, and synthesizing new teaching materials and strategies.

Adopt a people’s pedagogy.

The above suggestions for improving Reconstruction education all rest on the understanding that ordinary people can and do shape social reality. Traditional U.S. history writing and teaching, however, tend to frame the past as an almost inevitable series of events, rather than consistent moments of possibility and action at the grassroots level. In so doing, they obscure the agency of both ordinary people throughout history and students of history today. A people’s pedagogy, by contrast, shows students that although people are born into circumstances beyond their control, the ways they understand and navigate those circumstances impact the course of history. It is a far more active, participatory approach to learning how societies are inhabited and inherited.

A people’s pedagogy encompasses a variety of teaching strategies that foster critical thinking and bring history-making to life for students. A role play is one such exercise. Without performatively acting them out, students can take on roles that prompt intellectual consideration of the conditions and experiences of other people: What were their perspectives, what challenges and choices did they face, and how did their actions affect a course of events?

We feature these types of lessons at the Zinn Education Project. For instance, “Reconstructing the South” prompts students to imagine the experiences of freedpeople navigating the gap between liberation in theory and practice in the aftermath of the Civil War. They consider how African Americans in the South discussed and addressed critical issues like voting rights, land ownership, and education in a revolutionary struggle to turn freedom from an abstract idea to a lived reality. “When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible” gives students an opportunity to explore the rich social movements of the era by “meeting” a wide variety of late 19th-century activists at a Reconstruction mixer. They each take on a specific role and delve into the alliances and tensions between different causes — from abolition, to labor, to women’s rights — to learn about the profoundly democratic aims inherent to the project of Reconstruction and the ways racism and sexism severed its movements. By going beyond traditionally cluttered, one-dimensional textbook timelines and into these dynamic lessons, students and teachers alike may recognize not only the possibilities and challenges of Reconstruction, but also the choices they could make to drive justice today.

Implementing a people’s pedagogy also means encouraging students to scrutinize traditional mediums and methods of history education. Traditional textbooks may, for instance, pose as objective and authoritative while also relegating marginalized groups to the actual margins of the main narrative in colors and fonts that suggest their experiences are only supplemental. They may include Frederick Douglass’s admonishment of slavery and the hypocrisy of the Fourth of July as if it is somehow irrelevant to founding enslavers like Thomas Jefferson, whom they praise. Students should be taught to critique these framings and examine the contexts, audiences, and agendas that inform the presentation of history. Such pedagogy encourages historical consciousness — of exploitation and brutality, of justice and care, of the ways the past bears on people in the present.

State Assessments on Teaching Reconstruction

Footnotes

1Kate Masur and Gregory Downs, “Introduction” in The Reconstruction Era: Official National Park Service Handbook ed. Robert K. Sutton and John A. Latschar (Fort Washington: Eastern National Publishing, 2016), 19.

2Alabaman by Birth, “Elections in the South,” Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago, IL), Nov. 11, 1874, 2.

3Stacey L. Smith, "Emancipating Peons, Excluding Coolies: Reconstructing Coercion in the American West," in The World the Civil War Made, ed. Gregory P. Downs and Kate Masur, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 46-75.

4Rogers M. Smith, "Beyond Tocqueville, Myrdal, and Hartz: The Multiple Traditions in America," The American Political Science Review 87, no. 3 (1993): 549-66. Accessed June 9, 2021. doi:10.2307/2938735.

5Smith, "Beyond Tocqueville, Myrdal, and Hartz.”

6W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1935), 347.

7Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877 (New York: Harpercollins Publishers, 1988), xvii.

8Foner, Reconstruction, xx.

9Eric Foner, “Epilogue” in The Reconstruction Era: Official National Park Service Handbook, ed. Robert K. Sutton and John A. Latschar (Fort Washington: Eastern National Publishing, 2016), 179.