Rhode Island

Reconstruction Vignette

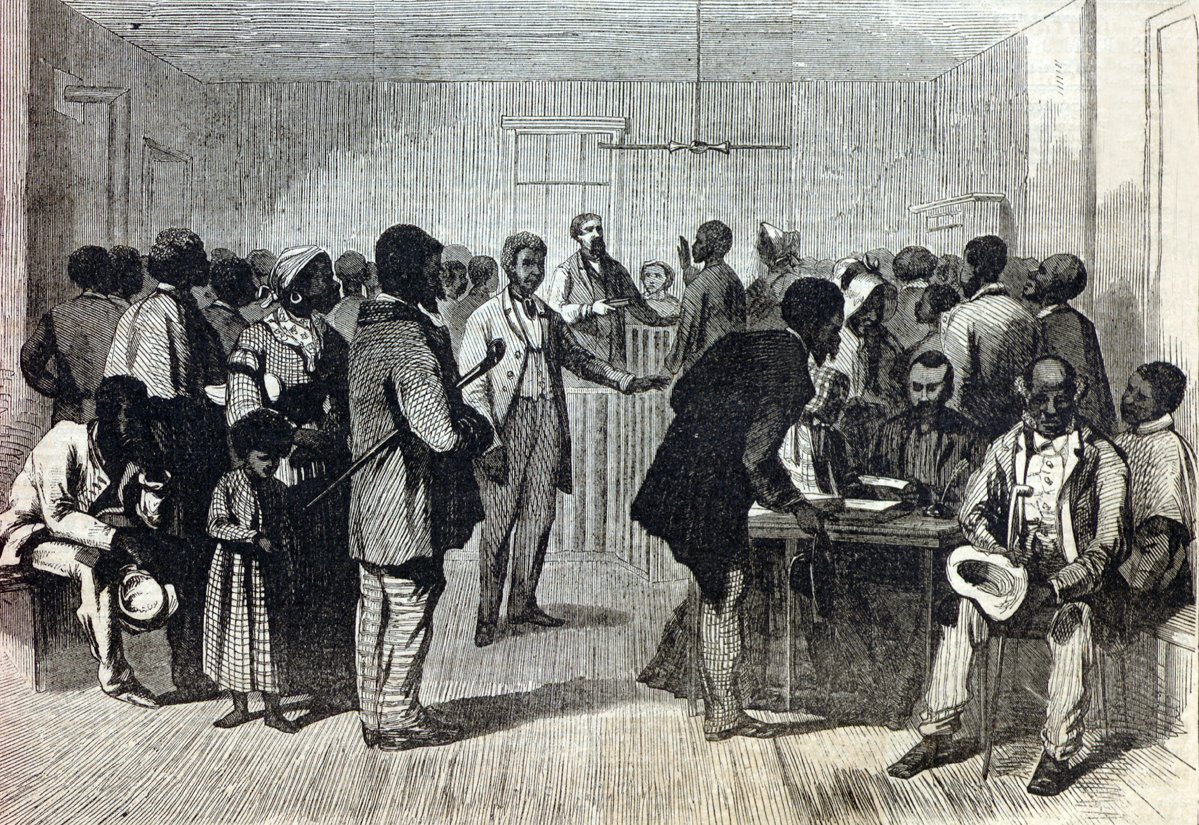

| Some Northern Blacks felt so betrayed and devastated by white indifference toward the welfare of African Americans that they could see virtually no hope for a brighter future. Writing to William Lloyd Garrison as “an able, consistent and influential friend of the colored race” following the 1876 election, Downing and several other Blacks in Newport, Rhode Island, poured out their pain and sadness about how Northern white Republicans they trusted and respected had turned their backs on African Americans. “We are depressed,” they confessed to Garrison, “things seem sadly out of joint; we are sick at heart through hope deferred. The declarations and advancements in civilization that are true of our country and that may be referred to make our condition deplorable. They make us more sensible as to the outrage we endure.” While these men were all too familiar with hatred and poor treatment from whites, what distressed them most was the indifference to their rights shown by leading New England men who had once been their collaborators and friends. African Americans could, they acknowledged, endure, “with a certain degree of complacency,” the insults they were constantly subjected to, but “the indifference as to the weak, as to our rights, and sympathizing with those who are outraging us. . . . make cold chills come over us.” |

George Thomas Downing (1819-1903)

Source: New York Public Library

A coalition of Black Rhode Islanders, including restauranter and civil rights activist George T. Downing, lamented the disloyalty of white political leaders in New England who revoked their support for Reconstruction in the mid-1870s.

Source: “We Will Be Satisfied With Nothing Less”: The African American Struggle for Equal Rights in the North during Reconstruction by Hugh Davis

Rhode Island

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Nonexistent

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 0 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Rhode Island’s standards is nonexistent. The Rhode Island Department of Education approved its standards, called the “Grade Span Expectations for Social Studies,” in 2008 and revised and expanded them in 2012. The standards are currently under review. Rhode Island is a local-control state, with curricular decisions made at the district level. The state standards are intended to capture only the “big ideas” of civics and history, not to provide a comprehensive curriculum.

Reconstruction is not included in the standards. Grades 5–8 standards cover the Civil Rights Movement and historical figures like Martin Luther King Jr. They cover the Bill of Rights and the Constitution as well as the concept of “states’ rights,” but do not mention Reconstruction. Grades 9–12 cover Rhode Island history during the Revolution, the qualifications for citizenship, “slavery and secession,” the “slave trade in RI,” “gradual emancipation and abolition,” and the Civil Rights Movement. Although there is relatively robust coverage of slavery in both the state and nation, there is little mention of the Civil War and no mention of Reconstruction.

Because Rhode Island’s standards provide so little information about whether and how districts and schools should teach Reconstruction, we chose to investigate curricula at the district level. The Local Snapshot below is not meant as a judgment of these districts’ approach to Reconstruction. They were chosen largely at random and are not factored into the grade the state standards receive. The brief analysis of district-level curricula that follows is intended to simply provide a snapshot into how state standards, or lack thereof, can shape Reconstruction pedagogy in the classroom.

Local Snapshot

Cranston Public Schools District

Grade 6

During the second quarter of the year, students in Cranston’s grade 6 social studies course take a unit called “Reconstruction/Industrial Age/Progressive Era.” The unit frames Reconstruction entirely as a political struggle waged by white people. The curriculum divides the era into three themes:

Radicals in Control: Protecting Freedmen’s Rights; 14th & 15th Amendments.

South during Reconstruction: Republicans in Charge; Carpetbaggers/Scalawags; Resistance; Education and Farming.

Post-Reconstruction Era: Divided Society; Jim Crow Laws; Reconstruction’s Impact.

High School

The Cranston High School history course overview that is available online provides little detail about which topics are taught in class. The Early United States history course encourages students to “trace the development of American politics, society, culture and economy and relate them to the emergence of major regional differences as they led to the American Civil War and Reconstruction and the healing of the United States.” Reconstruction is included in the curriculum as a portion of a unit focused on the “impact of the Civil War on the cultural, political, and diplomatic development of the United States.”

Though the Narragansett School System in southern Rhode Island does not publish detailed social science curricula, the information in their “Year at a Glance” summaries offers an interesting example of the guidance districts provide to teachers about how and how much they should teach about Reconstruction.

The final unit of the grade 7 course on United States and Rhode Island History is titled “Unit 6: Reconstruction: Freedom Comes at a Price” with a subheading “The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow.” The curriculum devotes 20 instructional days to this unit, compared to the 25 days that the Civil War receives.

The grade 11 U.S. history course devotes just 13 instructional days to both the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Educator Experiences

Rhode Island teachers responding to our survey reported that time and a lack of available curricular resources are the primary barriers to effectively teaching Reconstruction. Several teachers reported supplementing their curricula on Reconstruction with outside resources, including music, videos, and lesson plans drawn from museums and archives. Middle school teacher Christine Shaw wrote that expanding discussion of Reconstruction in high school is necessary “because [Reconstruction’s] graphic nature can be better conveyed at that age level.”

Assessment

Rhode Island’s state standards on Reconstruction are nonexistent. Although the standards specifically mention many historical events and topics, Reconstruction is not one of them.

At the district level, coverage of Reconstruction varies widely. The districts we examined all chose to make Reconstruction into its own unit in their middle school social studies courses. Both districts devoted far less time to it during high school. Teaching Reconstruction only in middle school limits how deeply teachers think they can delve into the topic. Given that Reconstruction is a key pivot point in U.S. history and so relevant to the character of the country today, it is important that students have the opportunity to grapple with its complexity at a high-school level.

Additionally, some middle school curricula contain problematic, misleading framings. In Narragansett, for instance, the unit on Reconstruction’s subheading is “The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow” — a perplexing description, as the fall of Jim Crow did not occur until the mid-20th century. In Cranston, the emphasis on “Carpetbaggers/Scalawags” embed approaches to Reconstruction that focus almost exclusively on white people, and reflect the cynical approach that characterize the scholarship of the discredited Dunning School. Troublingly, the category “Resistance” seems to refer to white supremacist terrorism, but the curriculum does not include the KKK as a term to learn. However, the curriculum does end with an assessment of “Reconstruction’s Impact,” which could provide an opening for teachers to discuss the positive and negative legacies of Reconstruction on U.S. history.

Without guidance around key Reconstruction-era history, many students will not learn about the intensification of white supremacy, the Black Codes, the KKK, debates over who would control land and labor, and Black agency and political organizing. Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In 2021, Rep. Patricia Morgan introduced HB6070, a bill designed to ban teaching about “divisive concepts” related to racism and sexism. The bill died in committee, but will likely be revisited. In 2022, Republican lawmakers introduced HB7539 to ban similar discussions and curriculum. Although neither bill has passed, their introduction is still troubling. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.