OREGON

Reconstruction Vignette

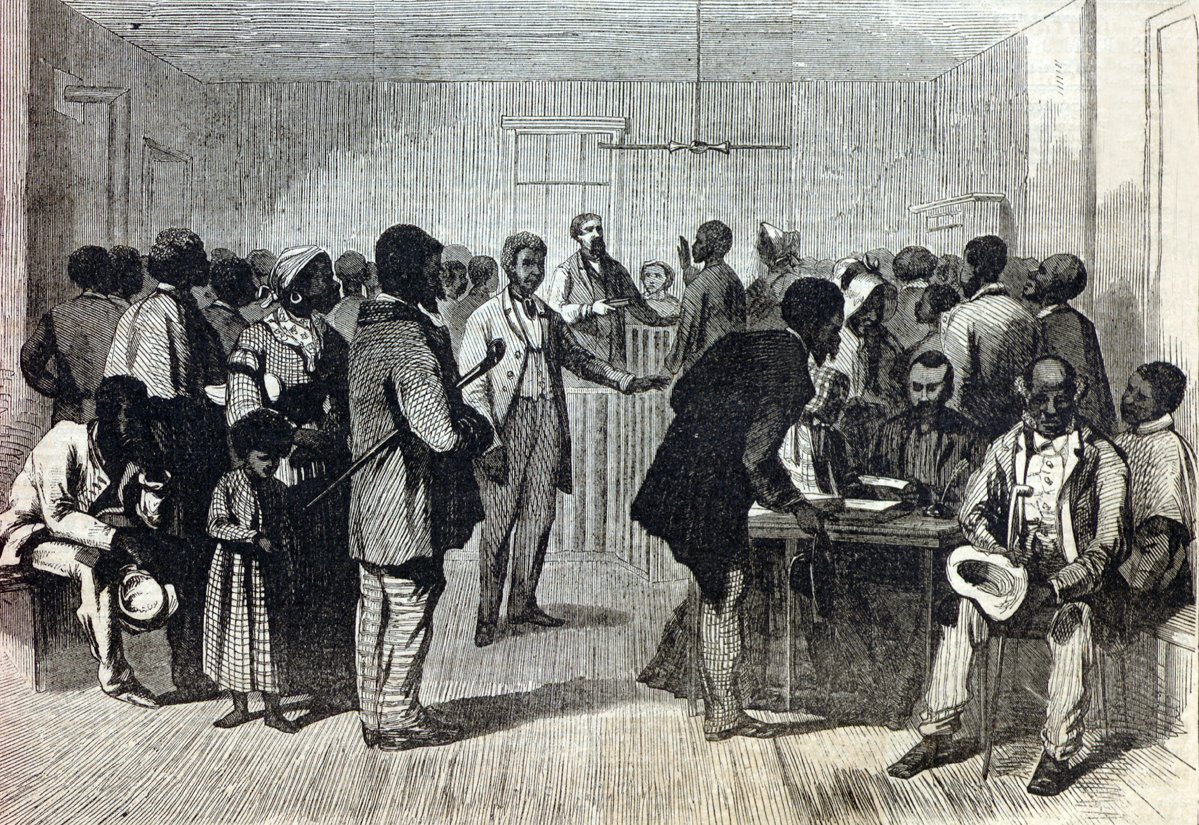

| It is tempting to dismiss questions about African American citizenship as irrelevant to postwar Oregon. After all, just 346 people of African descent lived in the state by 1870. When viewed in the larger frames of Oregon’s multiracial society and longstanding white supremacist legal regime, however, the threat posed by African American citizenship becomes clearer. White Oregonians worried that the seemingly imminent enfranchisement of African Americans at the federal level might lead to sweeping laws that prohibited all discrimination on the basis of race or color. African Americans may have been scarce in the Pacific Northwest, but Oregon was a multiracial state and home to thousands of American Indians, Chinese newcomers, Hawaiians, and mixed-race people. Oregon’s prewar laws excluded most of those non-white residents from exercising the rights and privileges of citizenship. At stake in the national debate over African American citizenship was the question of whether Oregon, or any state, could continue to make whiteness a central qualification for civil equality and political participation. |

In the 1860s and ‘70s, white Oregonians reaffirmed the state as a hostile place for African Americans to settle and barred thousands more people of color from civic life and citizenship rights. A Democrat-dominated state legislature took office in 1868 and quickly rescinded ratification of the 14th Amendment, which would not be ratified again until 1973.

Source: “Oregon’s Civil War: The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest” by Stacey L. Smith

Oregon

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Partial

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 1 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Oregon’s current standards is partial, and their content is dreadful. The newly introduced, presently optional, standards offer an improvement in terms of mentioning racism and underrepresented racial groups, but continue to provide little specific coverage of Reconstruction. The Oregon Department of Education adopted the current social studies standards in 2018. Beginning in February 2021, the Board of Education “adopted new social science standards integrating ethnic studies into each of the social science domains.” These new standards will become required in the 2026–2027 school year.

In both the current and the optional new standards, students are supposed to learn about Reconstruction in grade 8 and briefly in high school U.S. history.

Grade 8

The grade 8 course spans from 1776 to Reconstruction. Both sets of standards mention the Reconstruction Amendments and require students to “evaluate the continuity and change over the course of United States history by analyzing the key people and events from the 1780s through Reconstruction.” The new (currently optional) standards, however, include far more specific details about exploitative labor systems, the fight for citizenship, and legal structures of oppression than the current required standards.

Particularly relevant to Reconstruction, the new standards require students to “Examine and evaluate legal structures (e.g., Black Codes, Jim Crow, etc.) and Supreme Court decisions up to 1900 and their lasting impact on the status, rights, and liberties of historically underrepresented individuals and groups.” The new standards also reframe the Reconstruction Amendments as “significant documents establishing civil rights.” They also introduce a requirement to learn about the contributions and significance of “historically underrepresented groups in Oregon, the United States, and the world,” which could provide an opening to discuss Black activism and advancement during Reconstruction.

High School

Both sets of high school standards are equally broad for the course that spans “post-Reconstruction to the present.”

While there are no explicit mentions of Reconstruction in either set of standards, and the course ostensibly begins in the “post-Reconstruction” era, the new standards do provide opportunities for discussion of Reconstruction era themes and concepts, including:

Identify, discuss, and explain the exclusionary language and intent of the Oregon and U.S. Constitutions and the provisions and process for the expansion and protection of civil rights.

Analyze and evaluate the methods for challenging, resisting, and changing society in the promotion of equity, justice and equality.

Analyze and explain the historic and contemporary examples of social and political conflicts and compromises including the actions of traditionally marginalized individuals and groups addressing inequities, inequality, power, and justice in the U.S. and the world.

Identify and explain strategies of survivance, resistance, and societal change by individuals and traditionally marginalized groups confronting discrimination, genocide, and other forms of violence, based on race, national origin, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and gender.

Identify and analyze the nature of structural and systemic oppression on LGBTQ, people experiencing disability, ethnic and religious groups, as well as other traditionally marginalized groups, and their role in the pursuit of justice and equality in Oregon, the United States, and the world.

Educator Experiences

The overwhelming impression that Oregon teachers gave in their responses to our survey is that the state standards offer little guidance on teaching Reconstruction, but that individual schools and teachers have recognized its importance and sought to expand classroom instruction on the topic.

One middle school teacher explained that “the standards are so broad that an educator could skip Reconstruction and still technically ‘meet’ the standards.” Matthew Plies, a high school social studies teacher, explained that standards and schools “allow for teaching Reconstruction, but don’t require” it. Other educators detailed the difficulties that came from the placement of Reconstruction at the very end of grade 8 and a lack of district resources and support.

Assessment

Oregon’s current standards on Reconstruction are overly broad and do not center the era as a critical time period in U.S. history.

In many ways, the new, currently optional social studies standards offer a strong improvement. Their coverage of the systemic oppression of marginalized groups and how their resistance to that oppression has shaped U.S. society and history is particularly welcome. These standards would be greatly strengthened, however, by including specific examples of these themes drawn from the Reconstruction era. It would still be possible for a teacher using the new standards to entirely skip Reconstruction, simply by employing other historical examples of systemic oppression. The complexity, historical significance, and contemporary relevance of Reconstruction necessitate a dedicated study of the period in middle or high school, preferably both.

Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In 2023, Republicans introduced two bills designed to prevent schools from teaching about systemic racism or sexism. Both bills failed to pass, but their introduction is still troubling. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.