New York

Reconstruction Vignette

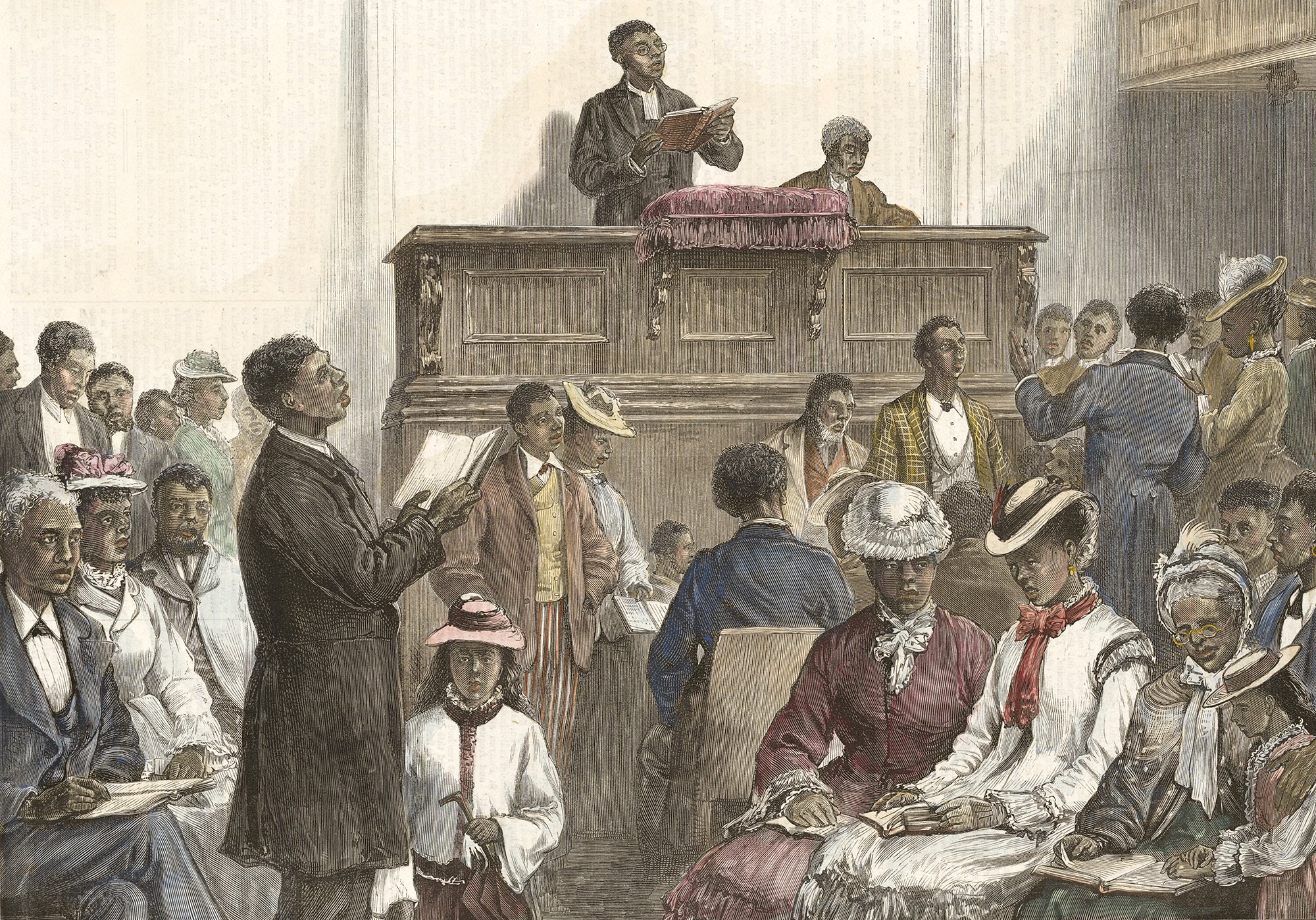

Henry Highland Garnet (1815-1882)

Source: Creative Commons

On Dec. 13, 1872, hundreds of African Americans convened in New York City for the first meeting of the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee. Cofounder Samuel Raymond Scottron read aloud a series of resolutions condemning the Spanish government for its enslavement of Cubans and delivered a speech, excerpted here. Reverend Henry Highland Garnet was the keynote speaker. By this time, Cuba had become one of the last countries to maintain slavery as a domestic institution, and protests from Cuban nationalists had ignited a revolution. The committee expressed a sense of responsibility and solidarity to those with fewer freedoms, drawing on a long history of Black activism in domestic and transnational anti-slavery societies as they championed Cuban revolts against enslavement.

Source: Colored Conventions Project

| Shall the four million in our own land, who have so lately tasted of the bitter fruit of slavery, stand idly by while a half million of our brethren are weighed down with anguish and despair at their unhappy lot? or shall we rise up as one man and with one accord demand for them simple and exact justice? Indeed, we look back but a very brief period to the time when it was necessary for other men to hold conventions, appoint committees and form societies, having in view the liberation of four millions among whom were ourselves; but, thanks to the genius of free government, free schools and liberal ideas, all the outgrowth of an enlightened and Christian age, we are enabled in the brief space of ten years to stand, not only as freemen ourselves, but with voices and with power to demand the liberation of five hundred thousand of our brethren, who are afflicted with the curse of human slavery. |

New York

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Extensive

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 6.5 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in New York’s standards is extensive, and their content is approaching adequate. The New York State Education Department’s Board of Regents adopted the current social studies framework in 2014 and revised it in 2016 and 2017. According to this framework, Reconstruction is taught in grades 8 and 11.

Grade 8

Reconstruction is covered in grade 8 in a course on U.S. and New York state history that spans Reconstruction to the present. The course examines the differences between Congressional and Presidential Reconstruction. Students learn about the Reconstruction Amendments, the “purpose, successes, and the extent of success” of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the effects of sharecropping, “the reasons for the migration of African Americans to the North,” and the “rise of African Americans in government.”

The course also focuses on the resistance and backlash to “federal initiatives begun during Reconstruction,” including the rise of Jim Crow and “the responses of some Southerners to the increased rights of African Americans, noting the development of organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan and White Leagues.” Students also examine how “the federal government failed to follow up on its promises to freed African Americans.”

Notably, the standards describe Reconstruction as having positive effects on Black people while noting that it was the challenges to Reconstruction federal policies that produced negative legacies for Black people. This is a distinction that few standards make.

Grade 11

Reconstruction is also included in the grade 11 standards in a U.S. history course that spans the colonial era to the 20th century. The section on Reconstruction focuses on the expansion of rights through the Reconstruction Amendments and how “those rights were undermined, and issues of inequality continued for African Americans, women, Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and Chinese immigrants.”

The high school standards also cover Black people’s struggles to secure their freedom, requiring students to “examine the ways in which freedmen attempted to build independent lives, including the activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the creation of educational institutions, and political participation.” The standards specify that students should understand the impacts of the Compromise of 1877 on African Americans. Though the standards do not specifically address white supremacy, they do mention the KKK and how Black people’s rights were “undermined by individuals, groups, and government institutions.”

Educator Experiences

A Brooklyn high school teacher explained that state standards do not present a barrier to teaching Reconstruction: the main obstacles are “timing, sequencing, and schools and the state wanting teachers to cover an adequate amount of material.” A middle school teacher in Hempstead noted that because the Reconstruction unit is “at the start of grade 8… the focus becomes the amendments and the focus of the end of Reconstruction instead of all the gains.”

Most respondents noted that the state standards offer “a solid framework” and do a “decent job summarizing and framing the Reconstruction era.” Many teachers, however, expressed concern with the content of the Regents Examination in Social Studies, which the state requires high school students to pass in order to graduate. This high stakes exam often guides teachers’ instruction. As one high school teacher from Waterloo explained, “having to cover all of U.S. history in one school year while also making sure students are ready for the end of the year test makes it difficult to really dive deep into any one particular unit.” Many respondents mentioned that “the test barely discusses Reconstruction.” A teacher seeking to ensure their students passed the Regents Exam, therefore, might choose to “gloss over” Reconstruction and focus on topics covered in more depth by the exam.

Assessment

New York’s Reconstruction standards are relatively robust and detailed. They cover the political, economic, and social transformations of the era and the racist backlash that followed in considerable detail. The standards’ focus on how Reconstruction and its defeat affected Black people is laudable, as is their attention to the promise of the Reconstruction Amendments and the many ways that promise was long unfulfilled. The middle school standard that differentiates the positive legacies of Reconstruction from the negative legacies of Reconstruction’s defeat is an especially strong standard that deserves emulation.

Areas to improve include more attention to the transformative nature of Reconstruction in the North and New York itself. More coverage of Black people’s grassroots advocacy for land reform, political power, and equality throughout the nation would also be welcome.

Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In August 2021, Republican legislators prefiled A8253, a bill for the next legislative session that would prohibit the teaching of “critical race theory,” the use of materials from the 1619 Project, and other subjects and resources that address systemic racism and sexism. In December 2021, Republican lawmakers introduced A8579, a bill that would prohibit “courses of study in critical race theory.” Neither bill passed, but their introduction is still troubling. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.