New Hampshire

Reconstruction Vignette

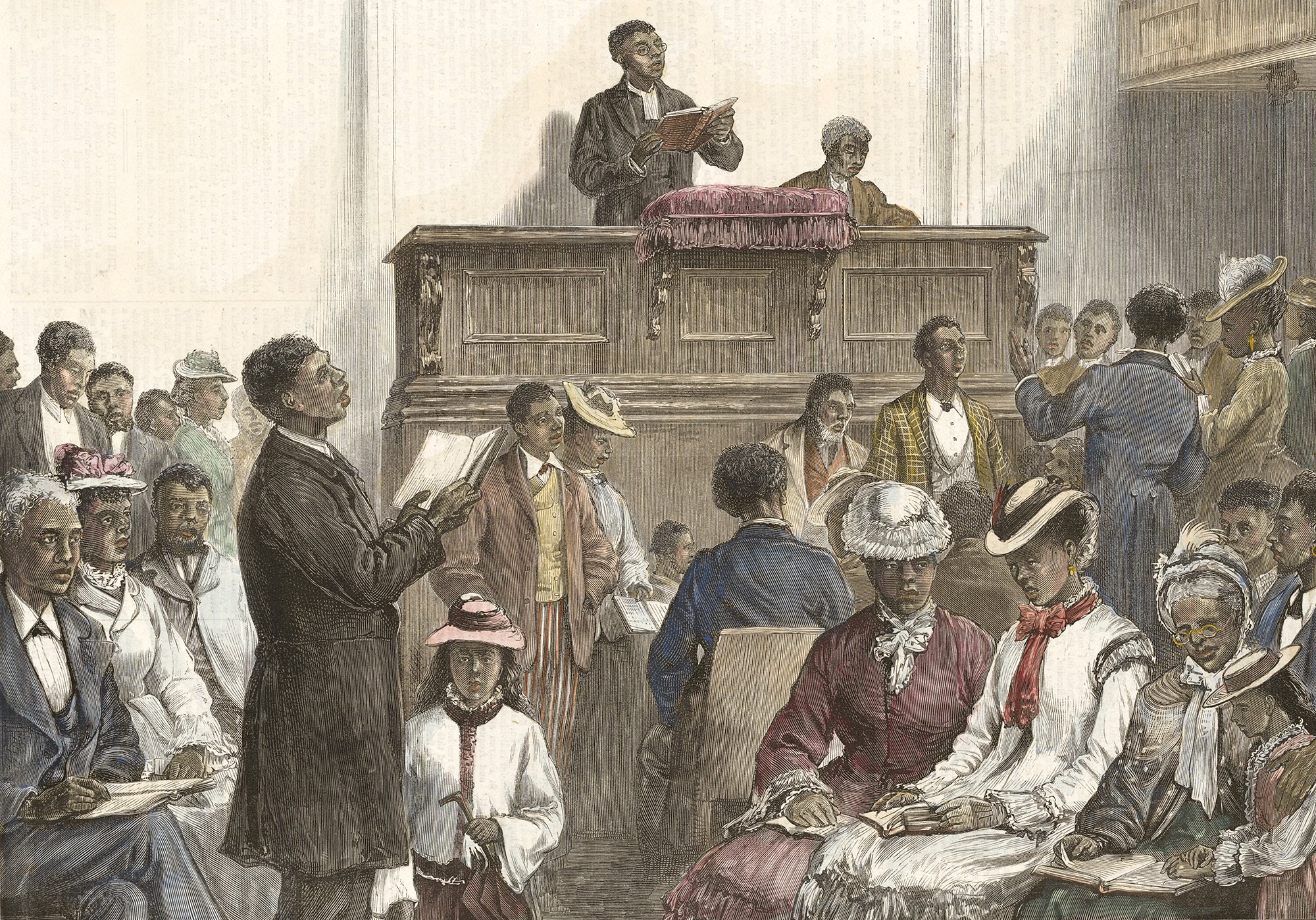

| Portsmouth’s Black citizens had been members of local churches since the 1700s, but there is no evidence of their attempting to establish a church of their own until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. A first, if not lasting, attempt was made in 1873. Under the leadership of Edmund Kelly a group of Portsmouth’s Black citizens gathered for worship in the Baptist tradition at the South Ward Room. The gathering flourished briefly. Then Kelly was “unavoidably called away” to Massachusetts. The group continued under the guidance of Elder John Tate. When Tate died a short time later services ceased. Not long after, Kelly returned to Portsmouth. . . . in 1879 Kelly reconvened Portsmouth’s fledgling church. |

Black residents of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, started to assemble their own church in the early 1870s. In the 1880s, a community known as the People’s Mission grew into another Black church organization that sustained services and programs well into the 20th century.

Source: Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage by Mark Sammons, Valerie Cunningham

New Hampshire

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Nonexistent

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 0 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in New Hampshire’s standards is nonexistent. The New Hampshire Department of Education adopted the current standards in 2006. The standards are currently under review. New Hampshire is a local-control state so curriculum decisions are made at the district level.

Reconstruction is not explicitly named in the current standards. There are 10 themes that students are expected to learn in U.S. history including “causes of the Civil War,” “evolution of and meaning of citizenship,” “slavery; racism; Jim Crow.” These are all areas where it is possible to talk about Reconstruction, though it is not clear from the standards that Reconstruction is, in fact, included in these areas.

Because New Hampshire’s standards provide so little information about whether and how districts and schools should teach Reconstruction, we chose to investigate curricula at the district level. The Local Snapshot below is not meant as a judgment of the district’s approach to Reconstruction. It was chosen largely at random and is not factored into the grade the state standards receive. The brief analysis of district-level curricula that follows is intended to simply provide a snapshot into how state standards, or lack thereof, can shape Reconstruction pedagogy in the classroom.

Local Snapshot

Reconstruction is a part of the last unit of the grade 8 social studies course in Nashua. Though grouped with the Civil War in the instructional unit, Reconstruction does have a set of dedicated learning objectives. They provide a generally top-down, political narrative of the era that does not center Black agency:

Slavery is abolished.

Civil War Amendments.

African Americans’ new legal rights.

The federal government stops enforcing civil rights laws (Jim Crow laws).

Educator Experiences

New Hampshire teachers reported using a variety of outside resources to extend their coverage of Reconstruction in the classroom including the Zinn Education Project and Facing History lesson plans.

In high school U.S. history courses, teachers made use of the Zinn Education Project’s Reconstructing the South lesson. Wendy Bergeron, a high school social studies teacher in Hampton, reported that the activity allowed students to “go beyond the political and experience Reconstruction’s impact on the people living at the time.” Note that Bergeron’s teaching here centers the organizing and activism of formerly enslaved African Americans, instead of only exploring the national political debates surrounding Reconstruction.

Several teachers explained in response to our survey that time pressures were a major factor in not teaching Reconstruction sufficiently. Teachers felt pressured to come up with creative ways to shorten instruction of other topics to get to Reconstruction and to convince their students that it is an important era to learn about and understand.

Assessment

New Hampshire’s standards on Reconstruction are nonexistent. The standards specifically name 10 topics and eras of study in U.S. history for students to learn about. These include slavery and Jim Crow, but not Reconstruction.

The lack of clarity in the state standards over when to cover Reconstruction has led some districts to include it in their middle school social studies curriculum while others place it in their high school U.S. history courses.

New Hampshire is currently in the midst of a lengthy and long overdue revision of its social studies standards. To improve coverage of the topic in the classroom, Reconstruction must be added to the list of main themes that districts are expected to cover.

Without guidance around key Reconstruction-era history, many students will not learn about the intensification of white supremacy, the Black Codes, the KKK, debates over who would control land and labor, and Black agency and political organizing. Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In June 2021, Gov. Chris Sununu signed HB2, a state budget law that bans teachers from discussing “the historical significance and existence of ideas and subjects” that include racism and sexism. In 2022, a bill to repeal the ban and another barring teachers from advocating “socialism” and “Marxism” both failed to pass. In May 2024, a federal judge struck down the original 2021 law, due to its vagueness on what topics teachers could not teach. Still, the introduction of such laws remains troubling.

Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.