Maine

Reconstruction Vignette

Click image to make larger

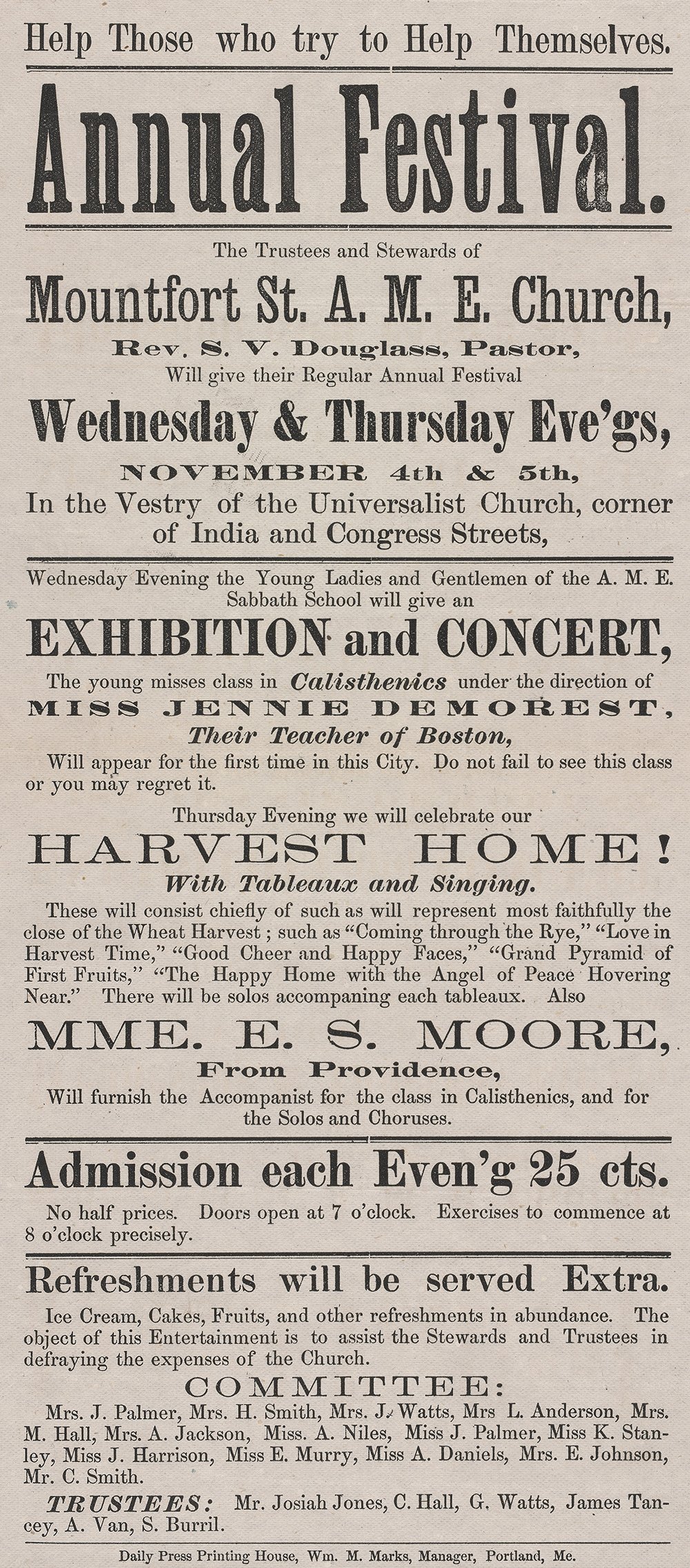

This broadside advertised an annual fundraising festival organized by an African Methodist Episcopal church in Portland, Maine. The November 1874 event included exhibitions and concerts starring children in the congregation, with a variety of refreshments served throughout.

Maine

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Nonexistent

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 0 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Maine’s standards is nonexistent. The Maine Department of Education approved the current social studies standards in 2019. The next review is targeted to start in 2023.

The standards are very broad and do not focus on specific content aside from national and state founding documents such as the U.S. Constitution, Declaration of Independence, and the Maine state Constitution. The standards do not mention Reconstruction. Even in the description of the chronological eras the standards cover, they label the 1844–1877 era as “Regional tensions and Civil War,” with no mention of Reconstruction.

The Department of Education does provide a link to the National Council for Social Studies’ C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards. However, the framework contains only one brief reference to Reconstruction in its glossary of terms as an example of a “Chronological Sequence” in history.

Maine is a local-control state so all curricular decisions are made at the district level. Because Maine’s standards provide so little information about whether and how districts and schools should teach Reconstruction, we chose to investigate curricula at the district level. The Local Snapshot below is not meant as a judgment of the district’s approach to Reconstruction. It was chosen largely at random and is not factored into the grade the state standards receive. The brief analysis of district-level curricula that follows simply provides a snapshot into how state standards, or lack thereof, can shape Reconstruction pedagogy in the classroom.

Local Snapshot

Grade 8

The town of Brunswick devotes three units of its grade 8 social studies course to “The Road to the Civil War,” “The Civil War,” and “Reconstruction.” The “Essential Understanding” of the Reconstruction unit is that “Reconstruction was an era of social, political, and constitutional conflict that had noble intentions but limited successes.”

Specific topics for study are largely political and include Lincoln’s assasination, Johnson’s impeachment, the Reconstruction Amendments, Reconstruction plans, and legalized discrimination. Two suggested essay topics, “how African Americans in the South lost many newly gained rights” and “describing the sharecropping system and how it trapped many in a cycle of poverty,” discuss white backlash to Reconstruction but omits the successes, short-lived though they were, of Black people in gaining political, civil, and social equality during the era.

Grade 11

The Civil War unit of the grade 11 U.S. History and Government course covers Reconstruction. The curriculum contains several learning objectives touching on Reconstruction:

The Civil War and Reconstruction resulted in continuity and change of government, economic, and social systems.

Like today, citizens in the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction were struggling with the role of government, human rights, equality, deep-seated societal problems, and the stratification of society.

Black rights were attempted to be upheld through this period through the actions of the 54th Massachusetts and the Freedman’s Bureau, and through the legislative measures of the Wade-Davis Bill, the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th Amendment, the 14th Amendment, and the Civil Rights Bill of 1866.

Additional teaching resources for the unit are entirely focused on the Civil War, not Reconstruction.

Educator Experiences

One high school teacher articulated the problem with the lack of state standards on Reconstruction clearly: “We really don’t have it in our school curriculum.” That omission, the teacher explained, “makes it difficult to fit into the small amount of time we have left in the semester of Early U.S. history after we teach other requirements.” Without more specific guidance, the teacher found it difficult “to keep students interested.”

Another Maine high school teacher said, “Reconstruction gets squeezed in between coverage of the Civil War and the Gilded Age and thus crucial elements like the failure of land reform are glossed over.” He had his students “research the ‘Slaughterhouse Cases’ and engage in a simulation which revealed how the Supreme Court's decision opened the door for gutting the 14th Amendment and paving the way for enshrining Jim Crow legislation.”

Assessment

Maine’s state social studies standards for teaching Reconstruction are nonexistent. Although it is not unusual for local-control states to have broad standards, the complete lack of any mention of Reconstruction is notable and unusual. It is particularly egregious that the standards define the 1844–1877 era as “Regional tensions and Civil War.” This vague framing obscures the roles of racial capitalism and slavery in U.S. history, as well as the coalitions of people who fought for or against these institutions. It also foregrounds the Civil War, understating the critical periods before and after it.

Districts are left entirely on their own to determine whether or how to cover Reconstruction. In Brunswick, for instance, a grade 8 prompt phrases the dismantling of Reconstruction as “how African Americans in the South lost many newly gained rights.” This framing is troubling, as it conceals the deliberate, white supremacist rollback of these rights behind a passive “loss” that could falsely assign blame for Reconstruction’s end to African Americans.

Without guidance around key Reconstruction-era history, many students will not learn about the intensification of white supremacy, the Black Codes, the KKK, debates over who would control land and labor, and Black agency and political organizing. Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In 2021, Rep. Meldon Carmichael introduced LD550, a bill designed to ban teachers from “engaging in political, ideological or religious advocacy in the classroom.” In 2023, Republican lawmakers introduced a bill that would ban teaching “critical race theory, social and emotional learning, and diversity, equity and inclusion.” All of these bills failed to pass, but their introduction is still troubling. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.