Hawaiʻi

Reconstruction Vignette

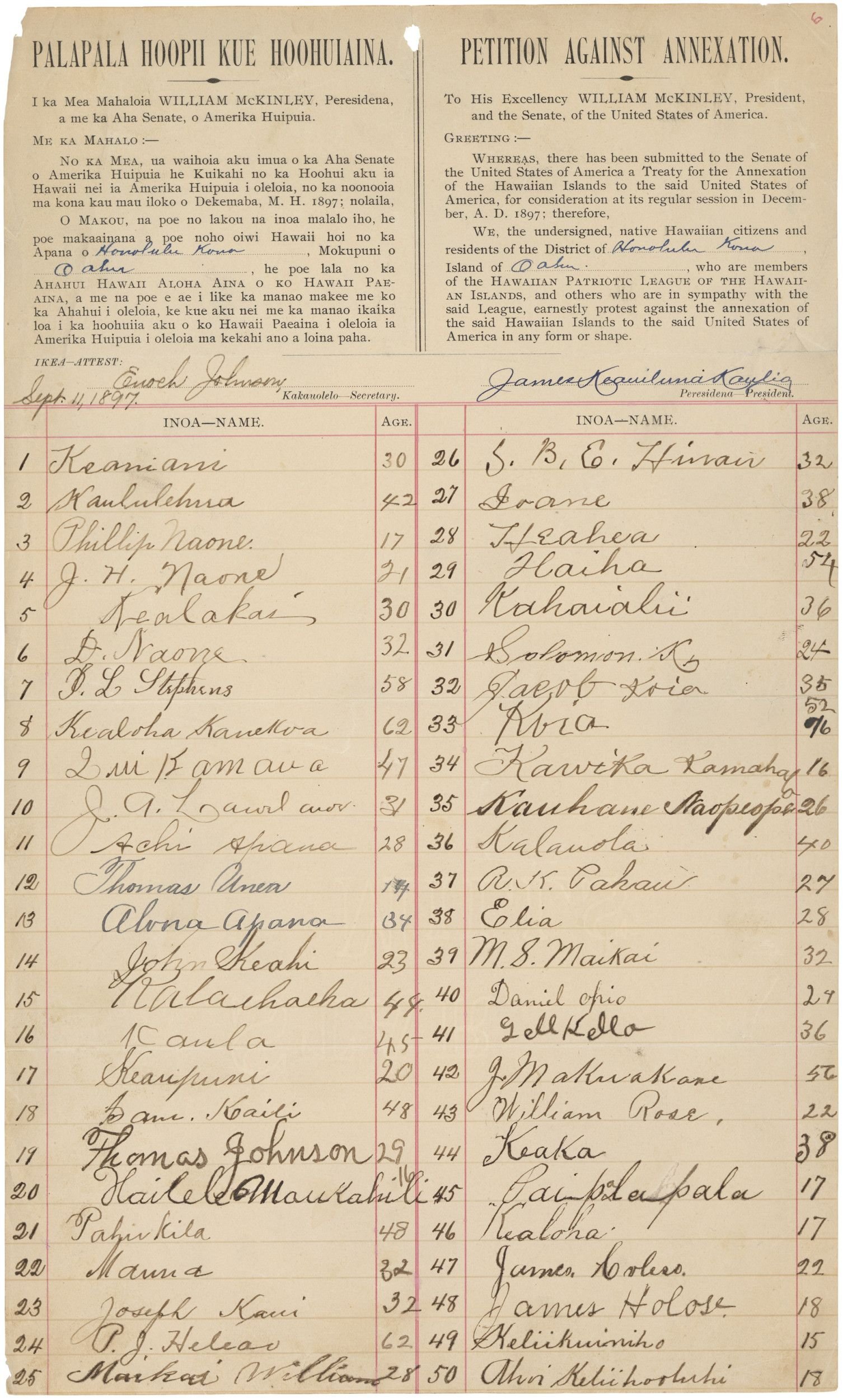

During the later years of Reconstruction, the federal government withdrew military power from the South and increasingly channeled it into western U.S. expansion and settler colonialism. Non-native white officials and industrialists in Hawaiʻi made plans to monopolize the islands’ sugar trade and other resources, increasingly pushing for annexation. In January of 1893, U.S. troops invaded the capital city of the Hawaiian Kingdom and incited a coup. They immediately helped these pro-annexation, non-native residents overthrow Queen Liliʻuokalani, who had recently issued a new constitution that would expand suffrage for native Hawaiians. As the United States moved toward annexation, the islands’ Indigenous people organized to assert Hawaiian sovereignty. This image shows one page of a petition that more than 21,000 native Hawaiians — over half of the islands’ Indigenous population — signed in 1897 to protest annexation. The United States annexed Hawaiʻi the following year.

Source: DocsTeach

Hawai’i

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Partial

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 7.5 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Hawaiʻi’s standards is partial, and their content is adequate. The Hawaiʻi Department of Education adopted the current Core Standards for Social Studies in 2018. The standards were written by Hawaiʻi social studies educators in collaboration with university faculty advisors. According to these standards, students learn about Reconstruction in grade 8 as part of a U.S. history course that covers from the Revolution to Reconstruction. A high school U.S. history course begins in 1880 with “Immigration and Migration.” While this unit mentions the Ku Klux Klan, it does so solely in the context of anti-immigration politics.

Grade 8

In grade 8, the standards are broadly organized around the “promise” and “repression” of Reconstruction. The section on promise asks students to “Assess the efforts of the federal government and African Americans to forge a new political and social order after emancipation” and to understand the rise of “repression and segregation” under Jim Crow.

The unit offers detailed Sample Content/Concepts to discuss:

Federal Action: Sherman Field Order 15, Presidential Reconstruction, Freedmen’s Bureau, Radical Republicans, Civil Rights Act of 1875, Reconstruction Amendments

Freedpeople: Black churches, Black officeholders, Black schools and colleges, Juneteenth

End of Reconstruction: Ku Klux Klan, Panic of 1873, racial terrorism, Slaughterhouse Cases, Compromise of 1877

Restrictions of Freedom: Black Codes, convict leasing, Jim Crow, Plessy v. Ferguson, sharecropping

Notably, the grade 8 standards explicitly mention “racial terrorism.”

Educator Experiences

A teacher who responded to our survey emphasized that the three weeks of instruction set aside for Reconstruction were insufficient to reach the depth necessary for true understanding.

One high school teacher explained that because the state is “not connected to the mainland United States. . . most students don’t relate to the topic.” This teacher sought to overcome this issue by connecting the themes of the Reconstruction unit to the story of Hawaiian annexation which was a more familiar topic for their students. The addition of primary source lesson plans and other outside resources to deepen Reconstruction coverage would be welcome.

Several teachers also mentioned pressure from parents who “don’t want us to discuss discrimination” as a potentially limiting factor. One middle school teacher described this as a major concern for lesson planning.

Assessment

Hawaiʻi’s social studies standards on Reconstruction provide relatively robust coverage of critical topics. They center Black agency, include white supremacist violence, and are clearly based on recent historical understandings of the time period. Inclusion of Sherman’s Field Order 15 in grade 8 also offers an opportunity, rare in state standards, for teachers to introduce discussions of land redistribution and the radical economic potential of Reconstruction.

Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

Hawaiʻi’s standards do frame Reconstruction as a critical moment in U.S. history. However, the standards lack a discussion of the positive and negative legacies of Reconstruction today and do not make clear connections to the history of Hawaiʻi. For instance, standards could connect Reconstruction-era Black political mobilization to native Hawaiian organizing against U.S. imperialism and the islands’ annexation in the 1890s.

The main concern that Hawaiʻi’s standards present is that this unit in grade 8 is the only time that Reconstruction is mentioned in the entirety of the K–12 curriculum. Because this is the very last unit of the year, teachers pressed for time may not make it to the topic, or will choose to discuss Reconstruction only briefly as the year winds down and standardized testing begins.