DELAWARE

Reconstruction Vignette

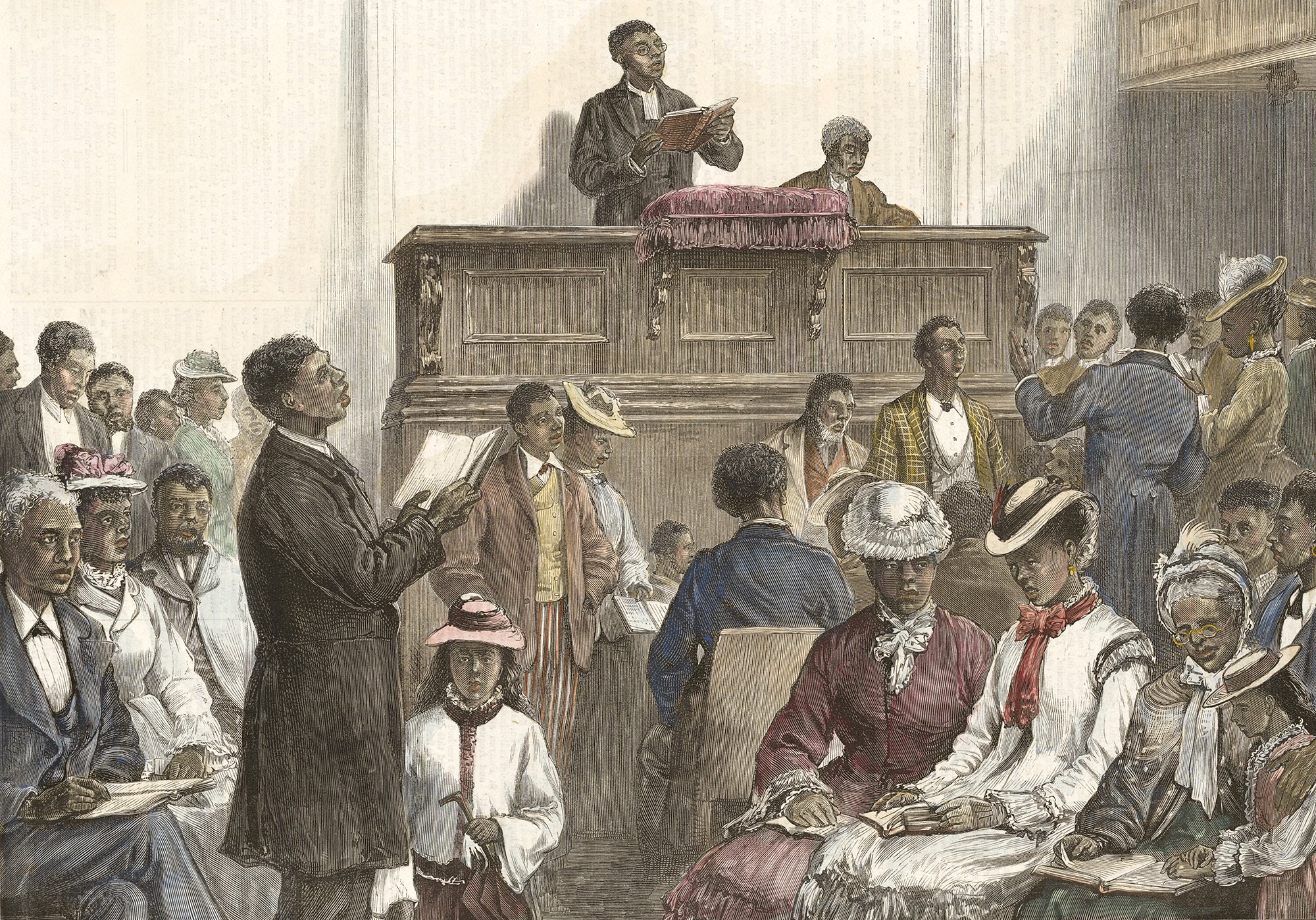

| From our population of over twenty thousand souls, or nearly one-fifth the entire population of the State, the Legislature does not provide a solitary school, nor appropriate a single dollar of State money. We hold this discrimination as against the genius of government; insulting to the laws of Congress; detrimental to the best interests of the State, and outrageous to the colored tax payers. We say against the spirit of the age, because non-progressive in its character and in the interests of ignorance; because tending to perpetuate poverty, multiply crime, and aid in human degradation. . . . This discrimination is outrageous to the colored people, because it is sullen opposition against their rights as citizens. It is founded upon no principle, backed by no argument, but sustained entirely by a prejudice founded upon a long course of false education. |

On Jan. 9, 1873, Delaware’s Convention of Colored People gathered in Dover to discuss and demand state provisions to educate their children. They adopted a resolution, excerpted here, condemning schooling discrimination in Delaware and asserting their rights as citizens and taxpayers to the benefits long provided to white residents.

Source: Colored Conventions Project

Delaware

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Nonexistent

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 0 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Delaware’s standards is effectively nonexistent. According to statewide curriculum guidelines created by the Delaware Department of Education, Reconstruction is covered in grades 6–8 and 9–12. Delaware is a local-control state and curricula are set at the district level.

State standards are broad and largely skills-based, providing no content examples of what students should learn. In grades 6–8, Reconstruction is likely covered under a standard that says “Students will develop an understanding of pre-industrial United States history and its connections to Delaware history.” In grades 9–12, Reconstruction is likely covered in a standard that says “Students will develop an understanding of modern United States history, its connections to both Delaware and world history.”

The state Department of Education’s recommended curriculum for grade 8 includes a “Civil War and Reconstruction” unit. This document describes “the volatile issue of Reconstruction” as being “as important as the war itself.” It also uses the term “unfinished revolution” to describe Reconstruction, a nod to modern scholarship on the topic. However, the seven instructional resources and six assessment resources included in the document are all about the Civil War itself or the causes of the war. None cover Reconstruction.

A Delaware social studies education associate reached out to us, noting that the state’s public-facing curriculum is quite limited. He shared more information on Delaware’s nonpublic-facing curriculum, which is available to teachers in the state and prompts far more discussion of Reconstruction than the recommended curriculum document mentioned above. For instance, teacher notes for a “Civil War & Reconstruction” unit include causes and effects of the following: the Reconstruction Amendments, successes and failures of Reconstruction, the emergence and reach of Jim Crow into the 20th century, and the Lost Cause mythology.

Because Delaware’s standards provide so little information about whether and how districts and schools should teach Reconstruction, we chose to investigate curricula at the district level. The Local Snapshot below is not meant as a judgment of these districts’ approach to Reconstruction. They were chosen largely at random and are not factored into the grade the state standards receive. The brief analysis of district-level curricula that follows is intended to simply provide a snapshot into how state standards, or lack thereof, can shape Reconstruction pedagogy in the classroom.

Local Snapshot

Grade 5

One unit in the social studies curriculum covers “The Civil War.” Although it does not explicitly mention Reconstruction, the “Essential Question” that students are supposed to be able to answer is “What are the lasting effects of the Civil War on the United States?” As it is written, grade 5 teachers could use these standards as a jumping off point to discuss Reconstruction as one of the “lasting effects” of the war, but it is not required.

Grade 11

Students in the grade 11 U.S. history course study the “Civil War/Reconstruction” as the very first unit. The only other guidance included in the published materials is that students are to learn from this unit “How can thinking like a historian help us to draw credible conclusions.”

Grade 8

The Colonial School District covers Reconstruction at the very end of grade 8. While Reconstruction is mentioned in the overall description in the course, it is not included as a discrete unit of study. Other topics that are contemporaneous with Reconstruction, “Westward Expansion” and “Industrialization, Antebellum, and the Civil War” are explicitly mentioned as units of study.

Grade 11

The high school U.S. history course begins in 1877, and so Reconstruction is not included in its scope.

Educator Experiences

Teachers surveyed on the topic emphasized that the curricular freedom they enjoyed in a local-control state allowed them to emphasize Reconstruction if they chose to do so. Ellen Ryan, a middle school teacher from Newark, was able to use outside lessons on Reconstruction from the Zinn Education Project and the Stanford History Education Group in her 8th grade history course.

Yet, as a New Castle high school teacher explained, teaching Reconstruction in middle school “limits the depth with which we can explore that era.” And with so many topics to address, teachers found they were often unable to “spend the needed time on Reconstruction.”

Assessment

Delaware’s state standards are so general and directionless as to be entirely impractical guideposts. Districts and teachers may delve deeper into the topic if they so choose. Because the statewide curricular framework provides the opportunity for schools to teach Reconstruction but does not mandate doing so, Delaware’s coverage of Reconstruction varies dramatically by school district.

Notably, the statewide standards, public-facing recommended curriculum, and district curricula we surveyed do not mention Black people either as individuals or as a group aside from passive descriptions of the “abolition of slavery.” This recommended curriculum offers a vague description of Reconstruction and does not provide teachers with resources to teach it in the classroom. The non-public-facing curriculum provides significantly more prompts and themes to incorporate. Still, the placement of Reconstruction at the hinge between middle and high school history courses may contribute to teachers deemphasizing the topic due to time constraints.

Without guidance around key Reconstruction-era history, many students will not learn about the intensification of white supremacy, the Black Codes, the KKK, debates over who would control land and labor, and Black agency and political organizing. Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In May 2021, the state House passed HB198, a student-designed bill mandating the inclusion of Black history in “all educational programming.” Although the bill does not explicitly mention Reconstruction, it would mandate all schools include the following topics in their curricula:

The relationship between white supremacy, racism, and American slavery.

The central role racism played in the Civil War.

How the tragedy of enslavement was perpetuated through segregation and federal, state, and local laws.