Arizona

Reconstruction Vignette

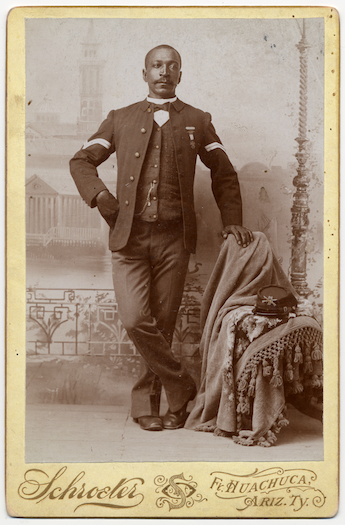

This is a cabinet card of Samuel Bridgewater, who joined the 24th Infantry Regiment in the 1880s and spent part of the 1890s as a Buffalo Soldier at Fort Huachuca in present-day Arizona. Buffalo Soldiers were members of postwar Black regiments, who the federal government deployed to the Great Plains and Southwest to support U.S. expansion and settler colonialism. They built infrastructure and defended U.S. settlements, often tasked with fighting Indigenous people in the name of a country that refused equal rights to people of color. Despite battling the Confederate insurrection during the Civil War and strengthening U.S. sovereignty during Reconstruction, Black soldiers faced white supremacist policies and terror from federal officials and civilians alike.

Source: National Museum of African American History & Culture

Arizona

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Partial

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 1 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Arizona’s standards is partial, and their content is dreadful. The Arizona Department of Education approved new state standards in social science education in 2018 and fully implemented them in 2020–2021. They were designed to be broad to “allow for the widest possible range of student learning.” As Arizona is a local-control state, school districts control “the sequence of instruction — what specifically will be taught and for how long.” Schools cover Reconstruction in grade 5 and high school.

Grade 5

The grade 5 course is titled “United States Studies: American Revolution [1763] to Industrialism [1900s]” and includes Reconstruction in a list of historical moments for suggested instruction in the course. The standards focus primarily on examples for teaching the Revolutionary period including the creation of the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights. The standards do not mention Black people, though slavery is referenced three times.

High School

The high school standards note students should learn about the “Civil War and Reconstruction including but not limited to causes, course, and impact of the Civil War on various groups in the United States, the impacts of different reconstruction plans, and the emergence of Jim Crow and segregation.”

Because Arizona’s standards provide so little information about whether and how districts and schools should teach Reconstruction, we chose to investigate curricula at the district level. The Local Snapshot below is not meant as a judgment of these districts’ approach to Reconstruction. They were chosen largely at random and are not factored into the grade the state standards receive. The brief analysis of district-level curricula that follows is intended simply to provide a snapshot into how state standards, or lack thereof, can shape Reconstruction pedagogy in the classroom.

Local Snapshot

Mesa Public Schools (Mesa Unified School District #4)

Grade 5

Arizona’s largest public school district, Mesa Public Schools covers Reconstruction in grade 5 for three weeks. The learning targets emphasize how the “outcome of the Civil War affected former slaves,” with references to various federal Reconstruction plans, formerly enslaved people’s difficulties in gaining full rights, and the importance of the Reconstruction Amendments. The curriculum also mentions the Reconstruction Amendments, land reform efforts, and several notable Black people by name. The curriculum does not mention white supremacy or the KKK, with the closest being a supporting question asking “What were some of the reasons many people in the southern states were unwilling to give former slaves full citizenship?” The overall thematic focus is on unification and rebuilding of the nation.

High School

The American and Arizona History course includes a “Civil War and Reconstruction” unit. The district’s high school curriculum covers Reconstruction in far less detail than the grade 5 unit. The three learning targets for the unit that discuss Reconstruction focus mostly on federal Reconstruction plans. One calls for students to be able to “relate societal changes and continuity of the Reconstruction Era to later eras.” The Key Concepts/Topics are equally broad, emphasizing Lincoln’s assassination, Reconstruction plans, and Black Codes and Jim Crow. Several sections offer openings to discuss Reconstruction, including discussing the “impact of the war on various groups” and “what actions did the government take to expand and protect individual rights in the Reconstruction Era?”

Tucson Unified School District

Grade 7

The first unit of the year in grade 7, “Civil War and Reconstruction” covers many of the essential topics and themes in Reconstruction with an emphasis on political conflicts. Required topics to cover include the KKK, Jim Crow, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the “Civil War Constitutional Amendments.” Recommended standards suggest that students should learn about the “change in status of freed slaves” and recognize that “Reconstruction was a period of conflict between the branches of government and the states.” The curriculum encourages students to discuss “What after affects (sic) resulted from Reconstruction that are still evident today?” and “Does racial equality depend on government action?”

High School

In Tucson high schools, Reconstruction is a small part of a unit titled “Westward Expansion, the Civil War, and Reshaping the Nation.” The focus is on national political and legal developments — Reconstruction plans, impeachment, the Reconstruction Amendments — but the curriculum also references the KKK, Compromise of 1877, and Jim Crow laws and requires students to analyze the “immediate and long-term effects of Reconstruction.”

Educator Experiences

Arizona teachers who responded to our survey emphasized that Reconstruction is “not prioritized in any way” in the state standards. Because “state standards do not specifically address or require discussions of Reconstruction as part of the curriculum,” many teachers reported that districts “watered down” the unit on Reconstruction and failed to make sufficient lesson-planning resources available to teachers.

Several teachers reported using the Zinn Education Project’s Reconstruction Mixer lesson in class, and one high school teacher from Phoenix created their own interactive activity for students to learn about voting rights inequalities.

The overall theme of the responses, however, was that although teachers want to expand their instruction, they often lack the time and resources to do so. One Tucson middle school teacher explained that they had resorted to searching for resources on Reconstruction on the internet. Lacking guidance on where to look, they “struggled to find resources that were appropriate for my students and their educational levels.” A high school teacher in Tempe had a similar experience and expressed that they would “like to do a better job of connecting Reconstruction era events and writings with contemporary issues” and were open to recommendations on how to do so.

Assessment

Arizona’s state standards on Reconstruction are effectively nonexistent and their content is narrow and insufficient. While vagueness in standards is expected in a local-control state, and may offer teachers discretion in how they approach a subject, districts will generally follow the guidance set by the state. In the above examples, both Mesa and Tucson followed the state standards in describing Reconstruction as a political and legal process. The lives and struggles of Black people to gain and redefine freedom is not a central part of the narrative of Reconstruction in their curricula.

Without guidance around key Reconstruction-era history, many students will not learn about the intensification of white supremacy, the Black Codes, the KKK, debates over who would control land and labor, and Black agency and political organizing. Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In 2021, Gov. Doug Ducey signed HB2898, a budget bill designed to restrict teaching about racism and sexism in the classroom. The Arizona Supreme Court declared these restrictions unconstitutional, and the state Department of Education declared them unenforceable. In 2023, Gov. Katie Hobbs vetoed a bill that included similar restrictions. Although these bills did not pass, their introduction is still troubling. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills can have, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.