ALABAMA

Reconstruction Vignette

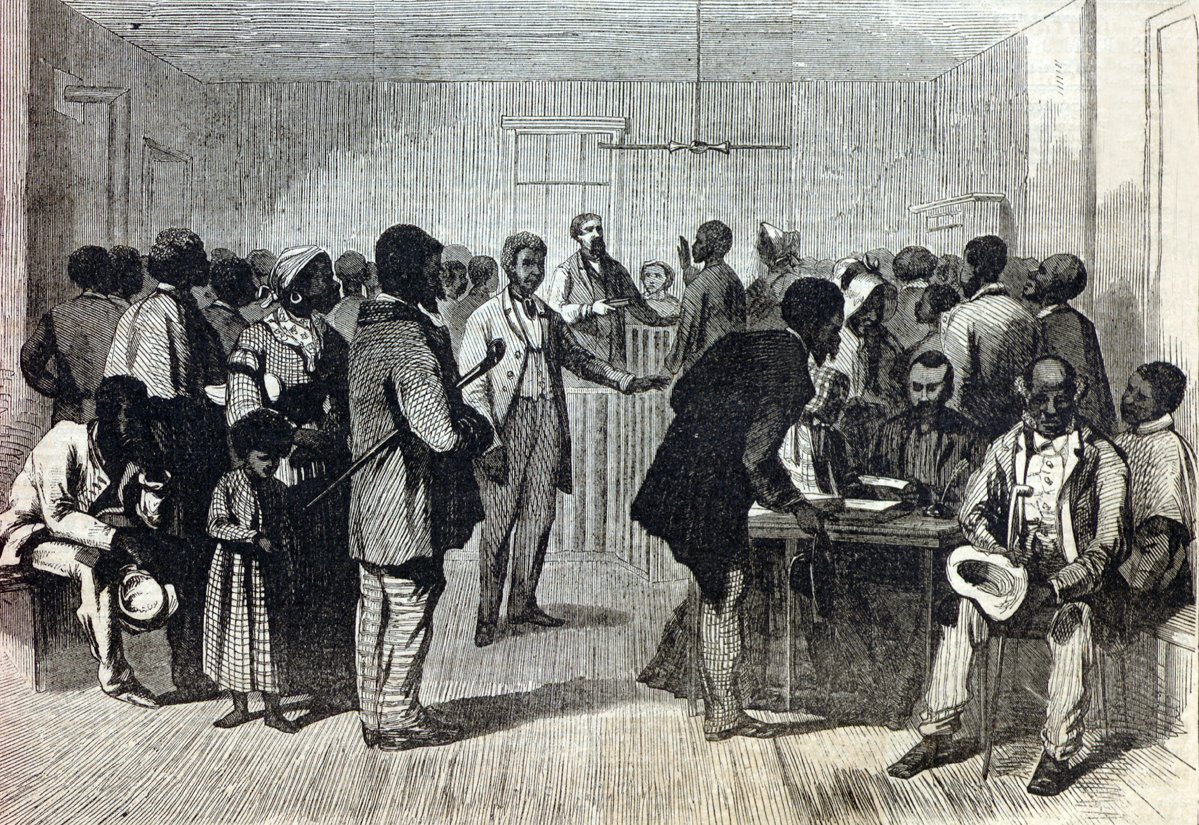

| Black Mobilians established a local newspaper, the Nationalist. They viewed sustaining a newspaper as essential to their quest for educational access and legitimacy. Although white American Missionary Association educators served as editors from Montgomery, the Nationalist had a trustees’ board composed entirely of African Americans and a few Creoles of color. In addition to news coverage, the newspaper placed an emphasis on literacy and citizenship building. John Silsby, the first editor, proclaimed that the advancement of literacy through a newspaper constituted the “new state of things.” He also promised that the Nationalist would contain “a variety of instructive and interesting matter. . . inculcating the truth that true religion and the virtues that germinate in it, are the only foundations of individual and national happiness.” To this end, the newspaper featured a children’s section, short stories, poetry, advertisements for literary societies and school events, and coverage of local, state, and national events. The Nationalist quickly became an important organ for Black Mobilians’ educational quest. |

In the fall of 1865, African Americans in Mobile, Alabama, established the Nationalist newspaper. It served as a vehicle for civil rights advocacy and community enrichment for the rest of the decade.

Source: Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865-1890 by Hilary Green

Alabama

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Extensive

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 1.5 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Alabama’s standards is extensive, but their content is dreadful. Alabama’s current social studies standards were adopted in 2015, and are accompanied by an older curriculum guide with instructional objectives of the standards. The standards were slated for revision in 2021, but state officials decided to delay this effort through 2027.

Reconstruction is most fully covered in grades 4, 5, and to a lesser extent, 10. Standards focus on politics and economics in grade 4, people’s lived experiences in grade 5, and state and national politics in grade 10.

Grade 4

Although the grade 4 standards on Reconstruction are extensive and relatively specific, Black people and their struggles for autonomy and freedom are not mentioned directly in the main standards. The goal of the unit on Reconstruction is for students to “describe political, social, and economic conditions in Alabama during Reconstruction.”

Standards ask students to “Define the roles of individuals such as carpetbaggers and organizations such as the KKK on the social and political structures of Alabama during Reconstruction.” The actors of Reconstruction in this narrative are white Northerners (carpetbaggers), white Southern Republicans (scalawags), and white Southern opponents of racial equality (members of the KKK). Black people are not actors in this narrative: Reconstruction happens to them; they do not shape it or participate in it.

Discussion of the Reconstruction Amendments and specific Black officeholders is relegated to the “Additional Content to Be Taught” section.

Grade 5

The grade 5 standards are briefer, but they do explicitly focus on Black people’s experiences during Reconstruction. One of the three learning objectives is for students to “explain how Reconstruction impacted lifestyles of women and African Americans,” which can provide openings for teachers to delve into discussions of the transformations that Reconstruction wrought throughout the South. Additional content includes examples like “voting rights for African American males, women as heads of households, stabilization of the African American family, role of self-help and mutual aid.” However, Reconstruction’s placement as the last unit of the year may shorten the amount of time and attention teachers devote to the subject.

Grade 10/11

Reconstruction appears near the end of the school year in grade 10 standards. The main focus of the unit is for students to “contrast congressional and presidential plans for Reconstruction, including African American political participation.” One of the main objectives is for students to “contrast the lives of African Americans and whites in the North and South after the Civil War.” Standards again single out scalawags as a group for students to learn about, but the focus of the course is on national politics.

In grade 11, Reconstruction is mentioned in a broader section on “Appraising Alabama’s contributions to the United States between Reconstruction and World War I.”

Educator Experiences

Teachers who responded to our survey noted that the main obstacles for teaching Reconstruction effectively in Alabama were a “lack of resources on the topic and sometimes lack of knowledge” about Reconstruction among teachers. Several teachers also mentioned concerns about “conservative/political backlash” and accusations of “indoctrination” potentially preventing them from delving deeply into contentious discussions of historical and contemporary racism.

Teachers mentioned using outside lesson plans and materials drawn from museums and the Zinn Education Project. One teacher specified that including Reconstruction in formal continuing education opportunities for teachers would greatly increase their own understanding of the topic and expose them to “a variety of resources to teach about Reconstruction.”

Auburn high school U.S. history teacher Dr. Blake Busbin noted, “One of the advantages to teaching Reconstruction in the state of Alabama is the incredible asset we have in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. This tremendously thought- and emotion-provoking memorial sparks critical reflection and discussion on the violence that plagued Reconstruction and the period following. It also allows students to begin deliberating on the purpose of monuments, such as what should and should not be memorialized, in contrast to the numerous Confederate monuments dotting the state’s landscape.”

Assessment

Though Alabama’s standards cover Reconstruction extensively, they emphasize white political conflicts. Black agency is present only in the optional additional content. The placement of Reconstruction at the chronological end of the courses in which it is covered also threatens to limit the amount of time teachers devote to it.

Black people, as a group or as individuals, play only a minor role in Alabama’s main educational standards on Reconstruction. This omission is reflected in the passive, limited, and flawed definition of Reconstruction contained in the standards’ glossary: “The period after the Civil War when the South was rebuilt; also the federal program to rebuild it.” Framing this period as “when the South was rebuilt” removes the choices and actions of human beings and obscures the debates about who it was rebuilt for: the formerly enslaved people or the former enslavers. The emphasis on white political actors in the main standards (carpetbaggers, scalawags, and the KKK) at the expense of Black advocates, politicians, and organizations presents a vision of Reconstruction as a struggle between whites.

Positively, the standards do highlight transitions from Reconstruction’s end to the emergence and impact of Jim Crow. Furthermore, the additional content in the standards is often excellent and contains specific references to Black people and their advocacy for rights and freedoms. Shifting that content into the main learning objectives could make major improvements to Alabama’s standards.

Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In October 2021, the state board of education voted to codify a resolution to ban schools from teaching “concepts that impute fault, blame, a tendency to oppress others, or the need to feel guilt or anguish to persons solely because of their race or sex.” Related legislation that would ban teaching about racism or sexism failed to pass in 2022 and 2023. But in March 2024, Gov. Kay Ivey signed into law SB129, which bars public schools and universities from maintaining any Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion offices or sponsoring related programs. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such measures can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.