North Carolina

Reconstruction Vignette

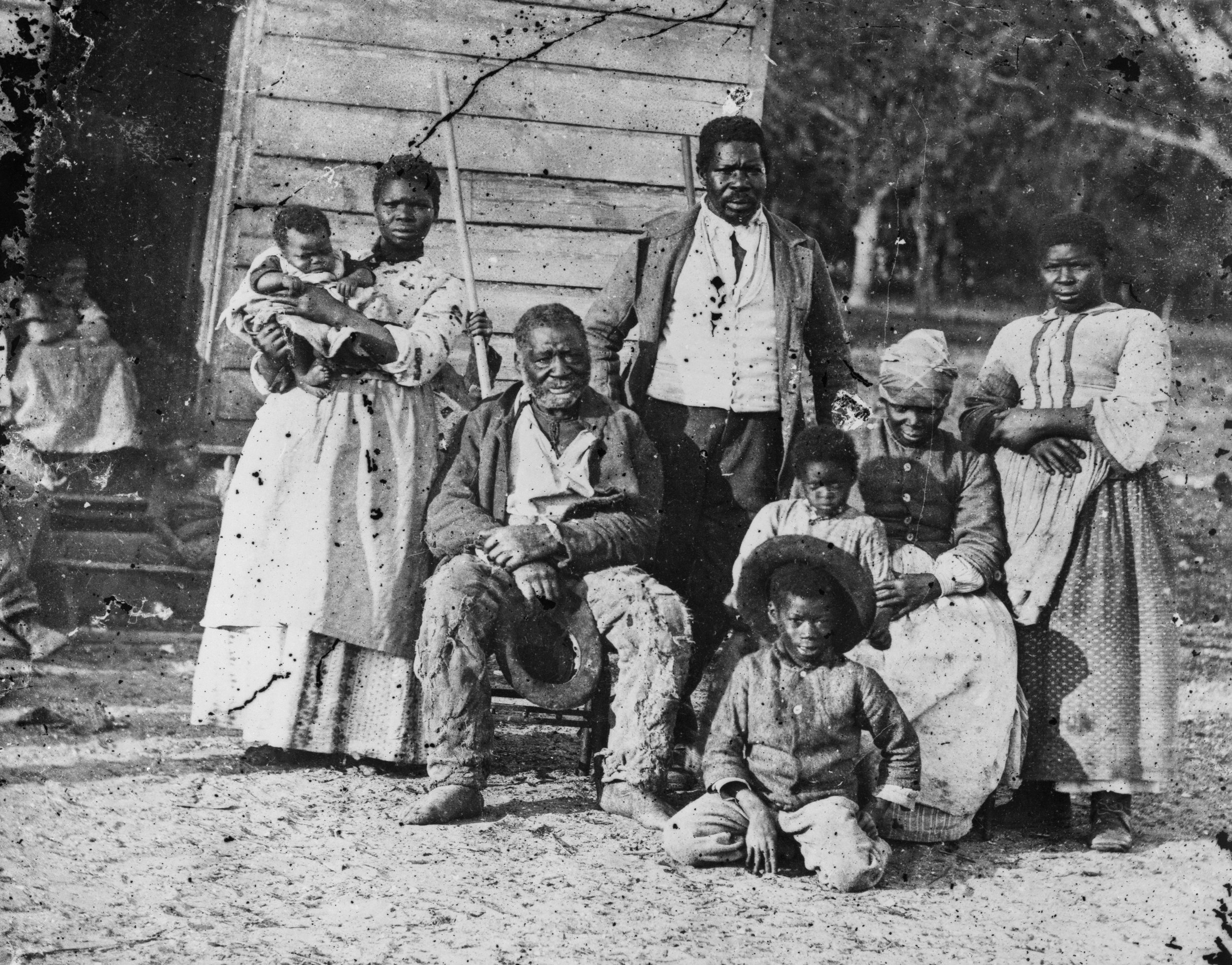

| By 1869, the chairman of the Committee of Freedmen’s Affairs estimated that smallpox had infected roughly 49,000 freedpeople throughout the postwar South from June of 1865 to December of 1867. This statistic tells only part of the story. Records of Bureau physicians in the field suggest that the numbers in their specific jurisdictions were, in fact, much higher. . . . Due to the countless freedpeople in need of medical assistance, many Bureau doctors claimed to be unable to keep accurate records. “I am unable to forward the consolidated reports of the sick freedmen for the month of February,” wrote a Bureau doctor from North Carolina. . . . In rural regions and in places where the Bureau did not establish a medical presence, cases went unreported. When the smallpox epidemic hit the area surrounding Raleigh, North Carolina, in February 1866, two freedwomen “walked twenty-two miles” in search of rations and support. The unexpected cold weather combined with the outbreak of smallpox in the state capital, however, depleted the Bureau’s supply reserve. After discovering that even the benevolent office had “only empty barrels and boxes,” and “nothing of real service to offer,” the women wept. Statistics fail to convey the great emotion and fear that the so-called pestilence incited among those living in the postwar South. |

In the 1860s, a smallpox epidemic erupted and devastated Black populations across North Carolina and throughout the South. The federal government largely neglected the medical crisis with ill-equipped, ineffective Freedmen’s Bureau hospitals and personnel.

Source: Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction by Jim Downs

North Carolina

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Nonexistent

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 0 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in North Carolina’s standards is nonexistent. It is worth noting that the new social studies content standards, approved by the North Carolina State Board of Education in February 2021, are a marked improvement over the previous standards in terms of coverage of themes of racism and injustice in U.S. history. However, because none of the standards actually mention Reconstruction while discussing these themes, the new standards receive a 0 on our rubric. The latest standards were contested by conservative opponents who argued that they “did not emphasize the study of enough of the country’s progress toward racial equity.” Advocates for the new standards emphasized that they would “ensure a more comprehensive and honest history was taught.”

The Reconstruction era is covered chronologically in grades 4–5, 8, and as part of the U.S. history course in high school. However, the word Reconstruction appears nowhere in the actual standards.

North Carolina’s standards are supplemented by “Unpacking Documents” that provide example topics, activities, and additional guidance for planning curricula. The grade 5, grade 8, and high school-level documents all list Reconstruction as an “Example Topic” to meet learning objectives. For instance, the grade 8 Unpacking Document cites “Presidential vs. congressional reconstruction” as a topic for students to consider “how debate, negotiation, compromise, and cooperation have been used in the history of North Carolina and the nation.” As another example, the high school-level document cites Reconstruction as a topic to explore when comparing “how some groups in American society have benefited from economic policies while other groups have been systemically denied the same benefits.” Analysis of primary sources related to the economic policies of Reconstruction is suggested as a “Formative Assessment” of this objective.

Grades 4–5

The grade 4 course focuses on local North Carolina history and the grade 5 course examines U.S. history but the standards cover similar questions and the same approximate time period. Although they do not mention Reconstruction explicitly, several of the learning objectives in both classes contain openings to discuss critical themes of Reconstruction:

Explain how the experiences and achievements of minorities, indigenous groups, and marginalized people have contributed to change and innovation in North Carolina/the United States.

Summarize the changing roles of women, indigenous, racial and other minority groups in North Carolina/the United States.

Grade 8

The state standards for the grade 8 “North Carolina and American History” course does not mention the word Reconstruction, but it does cover many of the critical themes of the period. Relevant learning objectives include:

Explain how slavery, segregation, voter suppression, reconcentration, and other discriminatory practices have been used to suppress and exploit certain groups within North Carolina and the nation over time.

Explain how recovery, resistance and resilience to inequities, injustices, discrimination, prejudice and bias have shaped the history of North Carolina and the nation.

Compare access to democratic rights and freedoms of various indigenous, religious, racial, gender, ability and identity groups in North Carolina and the nation.

High School

The high school American history course stretches from the French and Indian War to “the latest presidential election,” a formidable scope to cover in just one semester.

Learning Objectives that touch on themes of Reconstruction include:

Explain how slavery, xenophobia, disenfranchisement, and intolerance have affected individual and group perspectives of themselves as Americans.

Explain how various views on freedom and equality contributed to the development of American political thought and systems of government.

Critique the extent to which various levels of government used power to expand or restrict the freedom of American people.

Explain how racism, oppression, and discrimination of indigenous peoples, racial minorities, and other marginalized groups have impacted equality and power in America.

Compare how some groups in American society have benefited from economic policies while other groups have been systematically denied the same benefits.

Explain the causes and effects of various domestic conflicts in terms of race, gender, and political, economic, and social factors.

Educator Experiences

Nearly all of the North Carolina teachers who responded to our survey requested anonymity in doing so. Although many teachers across the country did so, as well, in North Carolina the fear of conservative backlash to discussing teaching the history of racism seems to have been particularly salient. One teacher explained that “many educators probably fear backlash from parents, schools, or even districts for teaching the real ‘hard history’ because so many people in the South don’t want to take responsibility for the past and the impact it has on today’s society.” Another mentioned “social obstacles” to teaching Reconstruction including “accusations of indoctrination” and a third referenced the “current political climate” as a concern when teaching Reconstruction. Possibly because of this fear, several teachers expressed that they generally “stick with the curriculum and root it in historical facts. I don’t do as much of the connections to [the] present day.”

Teachers bemoaned the lack of specific discussion of Reconstruction in the previous state standards and the lack of time devoted to the subject in class. One teacher expressed the need to “Rob Peter to pay Paul — take time away from other units we study in order to give them to the units that we feel are more significant.” Contributing to the time crunch is the recent decision by state legislators to reduce high school U.S. history to just one semester to accommodate a new Economics and Personal Finance course.

Despite the difficulties imposed by the previous state standards and the political pressure involved, educators reported using innovative approaches to teaching Reconstruction. Teachers have brought in a variety of primary sources and used outside teaching modules including the Zinn Education Project Reconstruction Mixer and activities from the Stanford History Education Group to supplement their instruction on Reconstruction.

Assessment

North Carolina’s coverage of Reconstruction is nonexistent. New state standards are a major improvement over the previous coverage of racism and injustice in U.S. history, but still contain significant shortcomings. Although neither the old nor new standards technically mention Reconstruction, the new standards effectively cover many important themes of the period. These standards, particularly at the high school level, can provide teachers and districts with a strong base to discuss the goals, achievements, and destruction of Reconstruction, as well as the ongoing relevance of the era.

These standards could be improved by including specific people and events from Reconstruction (e.g., the Reconstruction Amendments, Wilmington Massacre, Congressman George Henry White). It is essential to mention specific aspects of Reconstruction to ensure that teachers include the era in their lesson plans. A critical drawback of the new standards is the reduction of time for high school educators to teach U.S. history from two semesters to one. The largest concerns that teachers raised about teaching Reconstruction — insufficient time and a dangerous political environment for discussions of topics deemed controversial — continue to persist in North Carolina.

The supplemental Unpacking Documents contain specific references to Reconstruction that align with critical themes of racism and injustice across economic, political, social, and legal arenas. Noting these references in the standards themselves could make it easier for teachers to allocate time and resources to Reconstruction education.

Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In September 2021, Gov. Roy Cooper vetoed H324, a proposed bill designed to ban teaching about systemic racism and sexism. In 2023, a similar bill was introduced but did not pass. Although these bills did not become law, their introduction is still troubling. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such bills can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.

Moments in Reconstruction history

This short list of events in North Carolina’s Reconstruction history is from the Zinn Education Project This Day in History collection. We welcome your suggestions for more.

Feb. 1865: Black Town of Princeville, North Carolina Founded

Princeville, North Carolina originated in 1865 as a resettlement community for freed people.

March 1865 The Lowry Band Help Guide General Sherman on His March to End the Civil War

The Lowry Band helped guide General Sherman on his march to end the Civil War.

Feb. 1870: Wyatt Outlaw Murdered

Wyatt Outlaw, a Union veteran who became first Black town commissioner of Graham, North Carolina, was seized from his home and lynched by members of the Ku Klux Klan known as the White Brotherhood, which controlled the county.

Dec. 1895 Shaw University Established

Shaw University was established as a co-ed campus with support from private donors and the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands. It is the second oldest HBCU in the South.

The interracial, elected Reconstruction era local government was deposed in a coup d’etat in Wilmington, North Carolina.