Indiana

Reconstruction Vignette

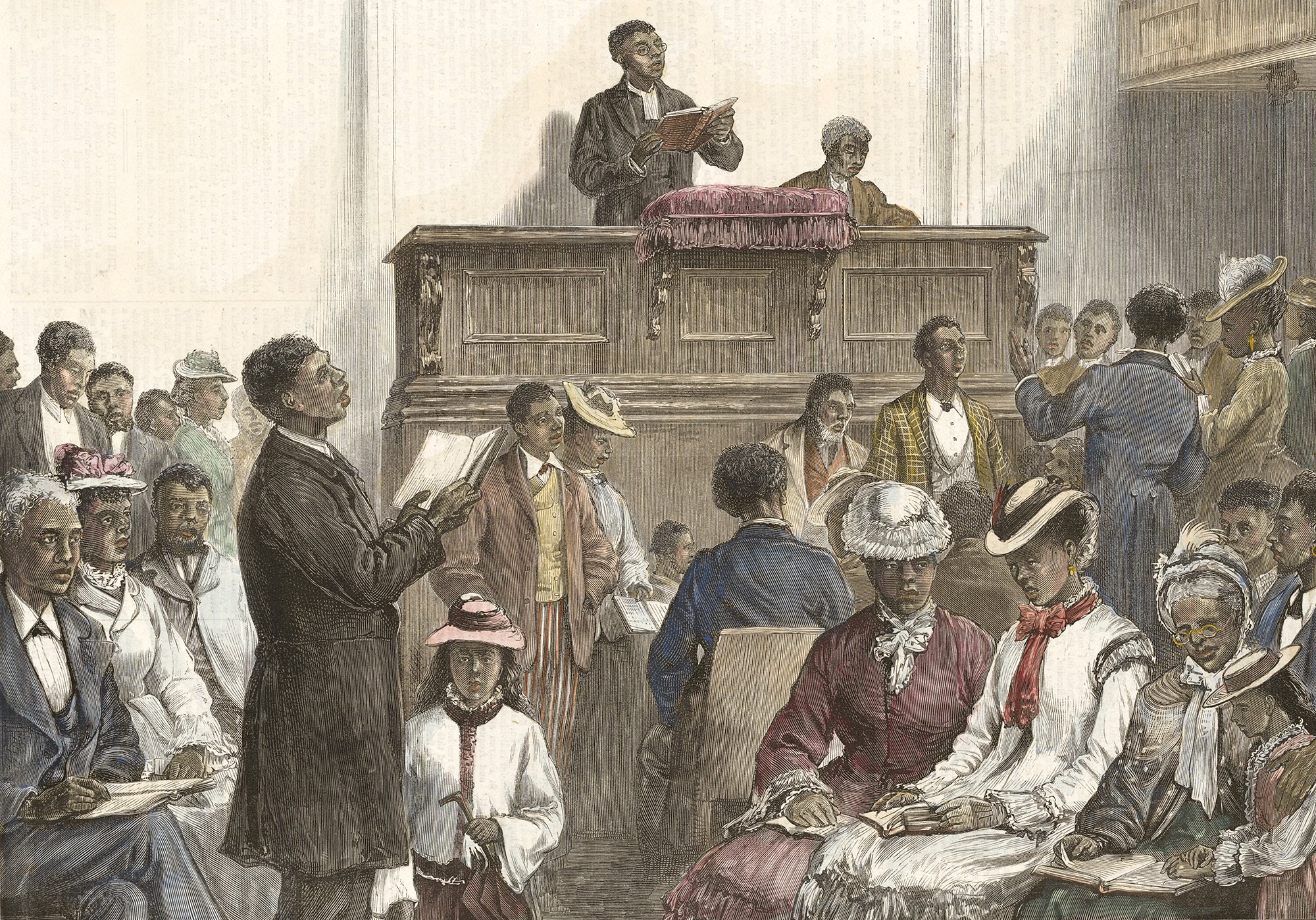

| The day after the Civil Rights Act passed Congress, in Lafayette, Indiana, a Black man named Isaac Barnes sued his employer, a hotel owner, for wages owed. The employer's lawyer claimed that Barnes was illegally residing in the state and therefore had no authority to make or enforce contracts there, and was not entitled to his wages. Were the racist settlement provisions in the Indiana Constitution still enforceable? A justice of the peace agreed with Barnes that they were not. The employer appealed to the county court, and there too he was defeated. . . . The judge observed that the Indiana Supreme Court had upheld explicitly racist laws in the past, as had the U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott. But, he argued, the Thirteenth Amendment had changed everything. Citing other people's doubts about the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act, he rested his decision on the amendment, which, he said, had swept away the “vile system” of slavery and required that “all the wrongs and oppressions built upon the wretched institution must cease.” Barnes, he concluded, was “a citizen of the United States,” fully entitled to the fruits of his labor. |

Indiana was the last Old Northwest state with traditional anti-Black laws intact, and they were still on the books when the Civil Rights Act of 1866 passed Congress.

Lafayette’s Isaac Barnes promptly used the power of this federal legislation to make gains at state and local levels.

Source: Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction by Kate Masur

Indiana

Standards Overview

Coverage of Reconstruction: Partial

ZEP Standards Rubric Score: 1.5 out of 10

The coverage of Reconstruction in Indiana’s new standards is partial, and their content is dreadful. In 2020, the Indiana Department of Education introduced new state standards for social studies education. According to these new standards, Reconstruction is taught in grade 8 and in a U.S. history course taught in grades 9–12.

Because the new standards have only just been implemented, we know little about how they shape teacher and student experiences in the classroom. The content of the standards regarding Reconstruction, however, is sorely lacking. For both grade 8 and high school U.S. history, the standards direct students to understand the “political controversies surrounding this time such as Andrew Johnson’s impeachment, the Black Codes, and the Compromise of 1877.”

The single sentence above, along with a learning goal in grade 8 for students to compare and contrast the various Reconstruction plans, is the extent of Reconstruction coverage in the Indiana educational standards.

The standards optional resource guide for teachers includes “supporting materials to help educators successfully implement the social studies standards.” The resource guide mentions the Reconstruction Amendments, the Civil Rights Act, and the rise of the KKK. It also includes guiding questions about Black people’s political, economic, and social rights during Reconstruction.

Educator Experiences

Teachers who responded to our survey affirmed that their textbooks gloss over important histories, instead skimming over the surface of most topics. Robert Urekew, a university professor, recalled his own high school Reconstruction education as “the story of the carpetbaggers and scalawags” with a classroom textbook that was “superficial and inattentive to the real issues of the time.”

Assessment

Indiana’s new standards fail to effectively cover Reconstruction. Missing from the required standards is any mention of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the Reconstruction Amendments, Black people’s political mobilizations and struggles for autonomy, or the violent repression of Reconstruction. By framing the period as a series of political struggles in Washington, D.C., the standards miss the radical promise of Reconstruction as ordinary Black people fought to redefine freedom and equality. For instance, the grade 8 and high school standard around “political controversies” centers white people as actors and Black people solely as victims, citing Andrew Johnson’s impeachment, the Compromise of 1877, and the Black Codes.

The supplementary resource guide contains good sources on these topics that represent a strong start for teaching Reconstruction, but it is unclear whether or how teachers will be able to make use of these optional resources. While many of the resources in the guide are excellent, the brief and narrow coverage of Reconstruction in the required standards may limit how much use teachers make of them. Its information is optional and still frames Reconstruction as a series of “political controversies” which may limit its effectiveness.

Teaching Reconstruction effectively requires centering Black people’s struggles to redefine freedom and equality and gain control of their own land and labor during and after the Civil War. Any discussion of Reconstruction must also grapple with the role of white supremacist terrorism in the defeat of Reconstruction and the negative and positive legacies of the era that persist to this day.

In 2022, Republican lawmakers introduced three bills designed to prohibit teaching about racism and sexism in public schools. SB167, HB1134, and HB1040 — which would require public schools to teach that “socialism, Marxism, communism, totalitarianism, or similar political systems are incompatible with and in conflict with the principles of freedom upon which the United States was founded.” They introduced similar bills in 2023 — all failed to pass. Still, their introduction is troubling. Several respondents to our survey expressed concern about the possible chilling effects on classroom education that such laws can have around the country, particularly on discussions of the history and legacies of Reconstruction.